What does the polling really say on Europe?

Welcome to the 94th edition of The Week in Polls, which is a bit of a behemoth as it dives head first into polling about the UK’s relationship with the European Union. It’s a big issue and there’s been a lot of polling, so grab a coffee, tea or hot chocolate and sit back…

Then it’s a look at the latest voting intention polls followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis. (If you’re a free subscriber, sign up for a free trial here to see what you’re missing.)

But first a weary glance of disappointment in ITV’s direction for mangling an all-too-rare proper poll about the views of British Muslims. We don’t get enough good polling on the views of different ethnic and religious minorities in the UK. Even huge sample MRPs rarely break out such crosstabs. So a particular shame that ITV managed to turn what should have been an interesting story about a drop in support for Labour among Muslims into a ‘how not to report a poll’ case study. It did this by getting the numbers wrong (comparing figures without don’t knows to those with don’t knows) and so running the untrue headline that claimed Labour’s support had halved. Cue pollsters rushing to tweet about how the media had got a poll wrong. At least the headline was then changed, the original tweet deleted and a new one sent.

As ever, if you have any feedback or questions prompted by what follows, or spotted some other recent polling you’d like to see covered, just hit reply. I personally read every response.

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

Already a reader and know others who might enjoy this newsletter? Refer a friend and you can get up to 6 months of free subscription to the paid-for version.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

The real story of polling on Europe

Let’s start with the easy stuff: hindsight.

What do people make of Brexit in hindsight?

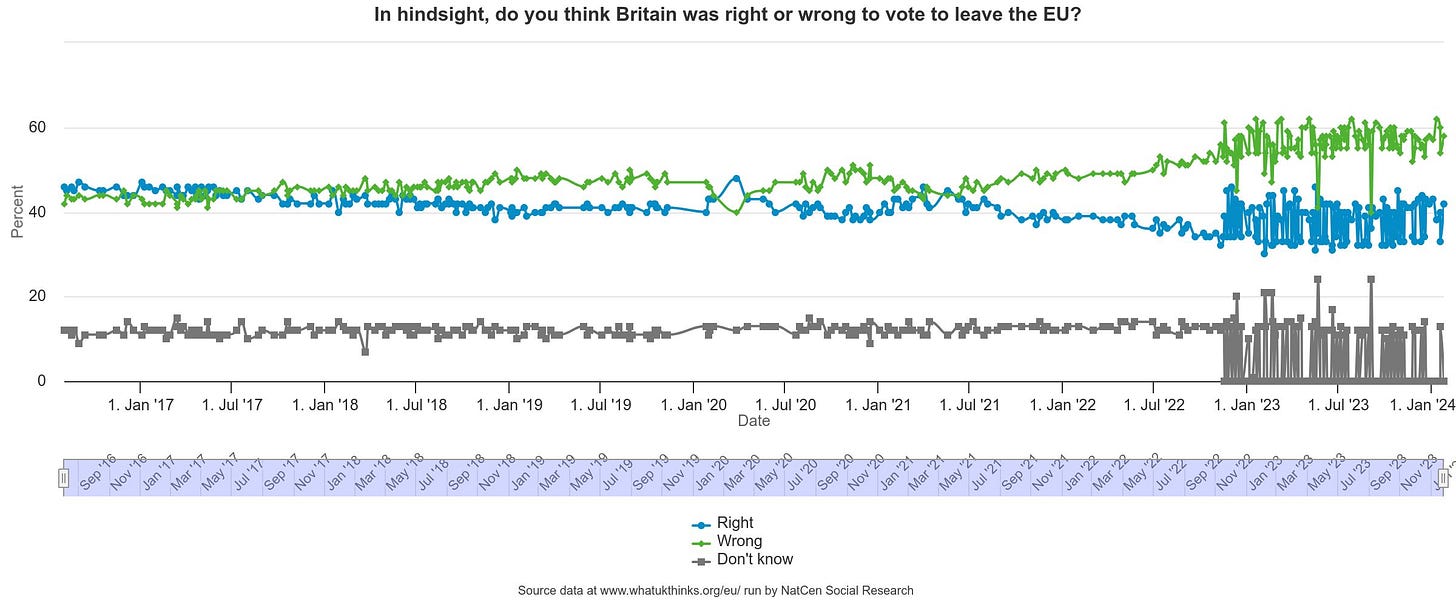

At time of writing, there have been 339 polls asking a version1 of whether, in hindsight, people think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU.

This graph shows the results:

The picture is consistent across pollsters: by January 2018 ‘wrong’ was in a small lead which largely continued until the middle of 2021. In the next year and a half, the lead for ‘wrong’ steadily increased, and for the last year it’s been fairly static with wrong averaging in the higher fifties.

Brexit is playing out as the opposite of changes such as the legalisation of same-sex marriage. On that, public opinion was somewhat divided at the time it happened, but then moved to sustained, strong support. Undoing the legalisation of same-sex marriage therefore now seems highly improbable, even as a long-term aspiration for socially conservative populists.

Brexit, however, is seeing opinion move in the other direction: against rather than in favour of the decision that had been taken.

Moreover, the younger the person polled, the more likely they are to say the Brexit decision was wrong. Taking the currently two latest polls in that graph, for example, Omnisis has ‘wrong’ at 34% among the 75+, rising to 69% among 18-24s, while for YouGov it is 38% among the 65+, rising to 64% among 18-24s.2

Of course, there are important things we don’t know. One is how the views of younger people will or won’t change as they age. Another is how the views of everyone may or may not change if there is a change of government.

At the moment, Brexit is fairly clearly associated with the governing party, so regret with Brexit may in part reflect, or be distorted by, unhappiness with the government. If there’s a different government, not so associated with Brexit, it may be that general unhappiness with the government doesn’t translate into Brexit regret and so those figures fall.

How strongly held are these views?

There are certainly some very passionate people when it comes to Brexit. However, the strength of feeling is, in some respects, fading:

In early 2020, right after the 2019 general election, 50 percent of the public told More in Common that how they voted in the Brexit referendum was important to their personal identity…

Polling in June 2023 however paints a different picture. Less than four years after our previous poll, the number of people saying that Brexit is important to their identity has fallen to 39 per cent. And Brexit-related identity has been narrowly overtaken by the 40 percent of people who say the political party they vote for is important to how they see themself. Politics as usual has started to reassert itself and Brexit as a point of political discord is becoming less polarised.

Note also that ‘ashamed’ didn’t reach 50% in this poll:

Even so, ‘ashamed’ was the most popular option, and it’s clear that in terms of public opinion, Brexit has not been a success so far.

Or as one professor of political science put it, amongst others:

Moreover, there are hints that we may be seeing an asymmetry emerge, with those unhappy with Brexit holding those views more strongly than those in favour of Brexit:

After the 2019 election the number of Leavers and Remainers who said that Brexit was important to their identity was the same at 50 per cent, respectively. Today, the number of Leavers who say that Brexit is important has fallen by 19 points, but the number of Remainers who say the same has fallen by just four points. In short, what persists of “Brexit Identity” is being driven in large part by Remainers.

That may change if Brexit were seen to be seriously under threat, mobilising Leavers to feel more passionate. But again it points to a picture of Brexit not being a done deal forever.

Why have people’s views changed so far?

Why has there been this rise in Brexit regret, Bregret? Simply because people think Brexit hasn’t gone well:

Again, there’s a consistent age pattern, with younger people being more negative about Brexit, such as with Ipsos finding that 7 in 10 of the under-35s think Brexit has been a failure.

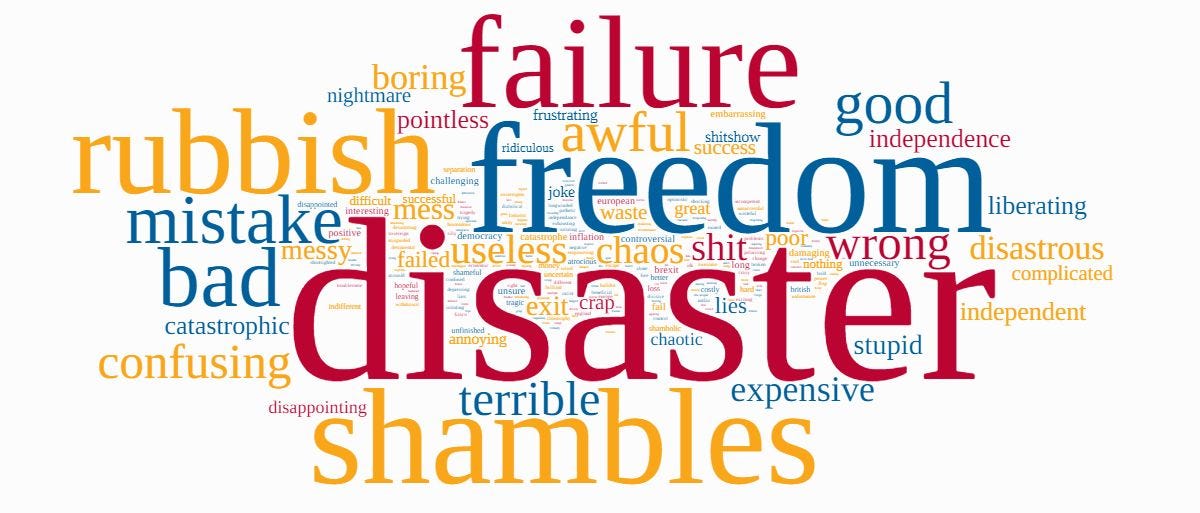

Or in wordcloud form, based on people being asked to sum up Brexit in one word:

No surprise then that the government’s handling of Brexit consistently gets a big thumbs down:

Moreover, to give one of the many examples from other pollsters, even Leavers aren’t enamoured with how Brexit is going:

Seven years on from the referendum campaign, the pollsters Public First asked more than 4,000 Leavers how they felt now about Brexit. Less than a fifth of them – 18% – said it had gone well, or very well, while 30% said it had gone neither well nor badly, and 26% said it was still too soon to say.3

The role of immigration

Part of the story with Leavers being unhappy with Brexit is what has happened with immigration since.

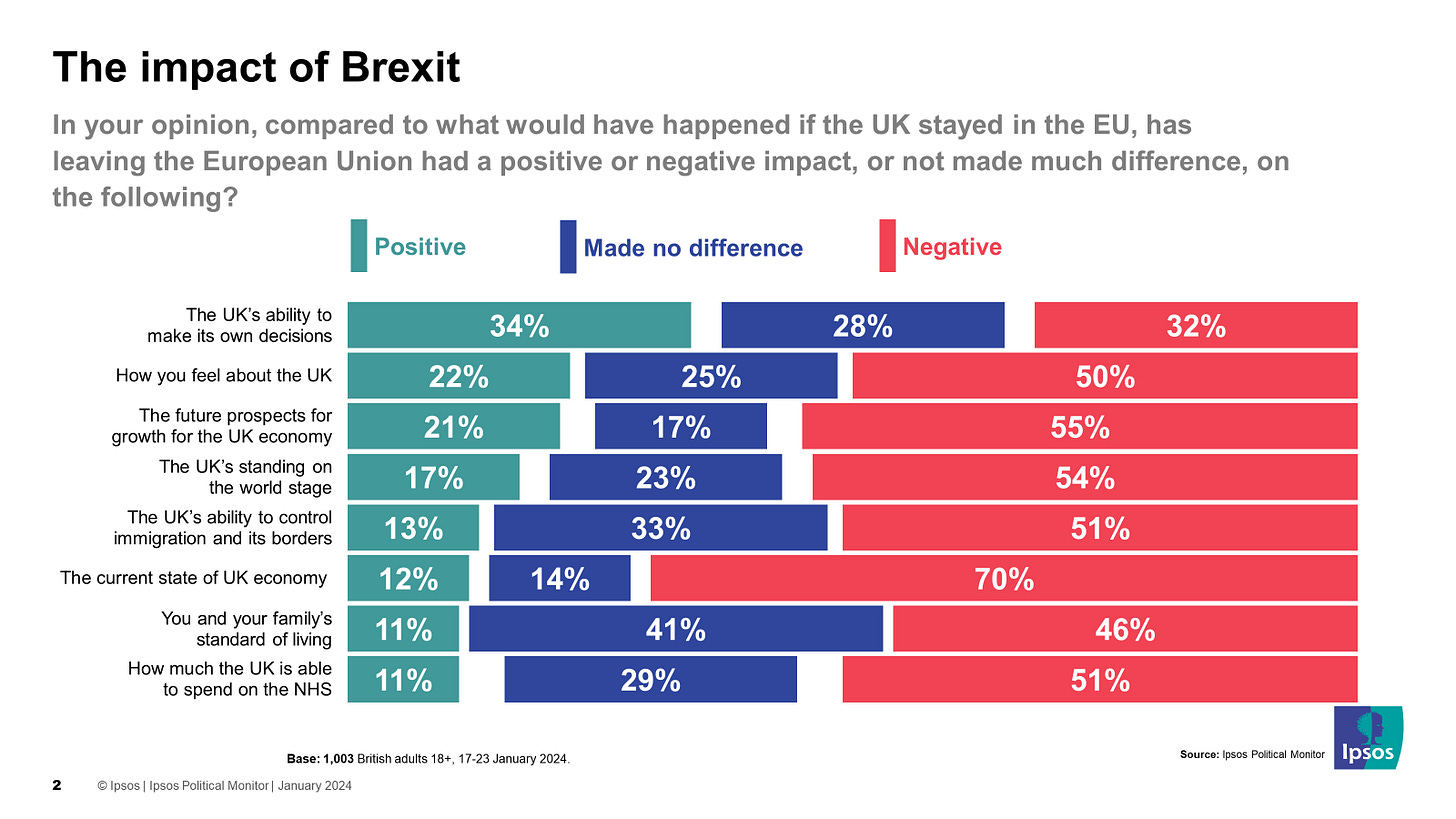

Note the mere 13% saying Brexit has had a positive effect on immigration and border control:

Or from another poll:

Half of voters believe Brexit has made it harder to solve the Channel migrants crisis, poll says

More Leave voters believe quitting EU has made it harder to deliver effective asylum policy despite Brexiteer pledges to “take back control” of UK borders.

Again that should make us wonder a little about what future events might do to attitudes towards Brexit. Will a future government that is seen as more successful on immigration result in fewer Leavers being unhappy with Brexit?4

But it’s not all about immigration, as 70% (!) say Brexit has had a negative effect on the economy and even 51% saying it has had a negative effect on the ability to fund the NHS. The days of that £350 million bus seem to be well behind us.

What do people want to see happen as a result of Brexit’s failure?

There are two very different possible follow-ups to thinking that Brexit has not worked out well.

One is to blame Brexit itself, which might lead to support for moderating or undoing it. The other is to blame British politicians and/or the European Union for not doing Brexit properly, which is more likely to lead to support for continuing or hardening it.

So where does public opinion sit on what should be done?

Hypothetical referendum answers

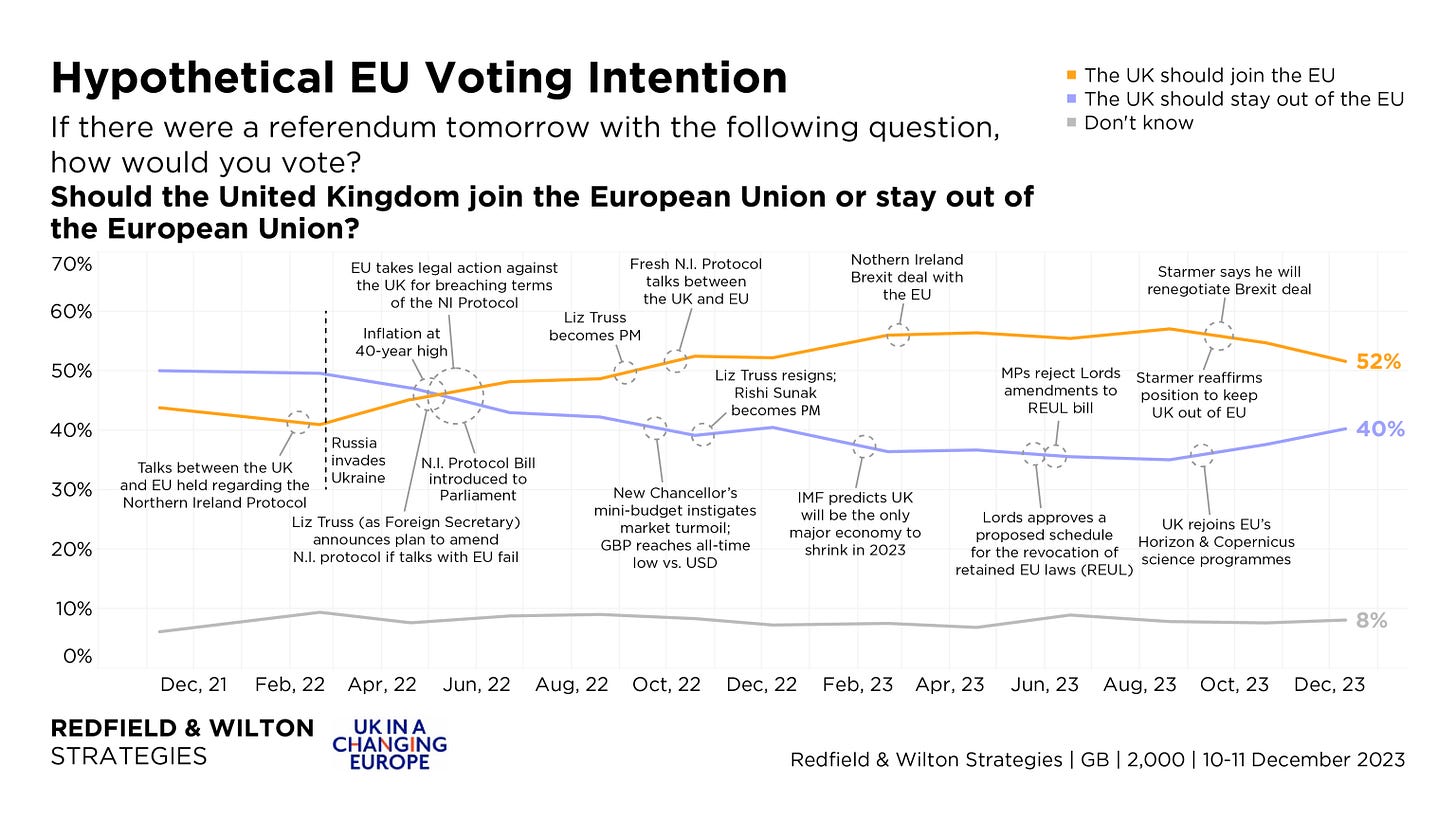

There’s quite a volume of polling showing that, given a straight-forward hypothetical referendum to think about, people would vote for Britain to rejoin the EU. Take the Redfield & Wilton tracker, for example:

But scratch under the surface, and things look much less sure, due to history, softness and reluctance.

A warning from history

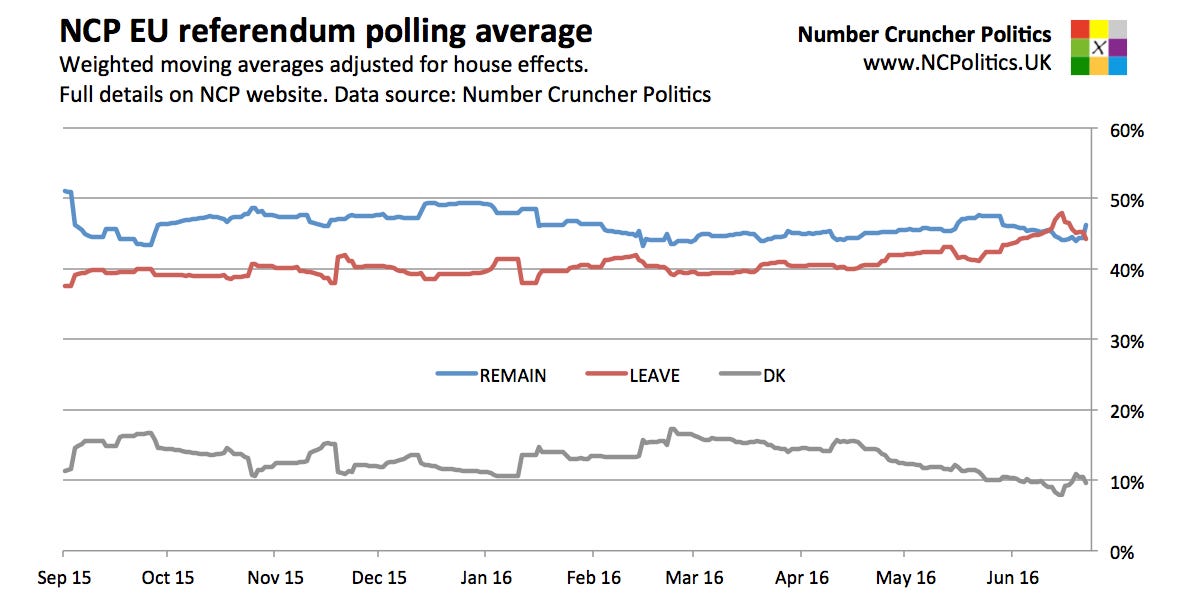

History first: in the run-up to the 2016 referendum, remain was for a long period consistently ahead in the polls and by a similar magnitude to what we’re currently seeing. We know how that story turned out.5

Or there are lessons from the Alternative Vote referendum - many years of public support for electoral reform followed by a huge vote in favour of first past the post when put to the test.

Or the 2019 Parliamentary Petition to revoke Brexit. Over six million signatures and then support for revoke not followed through on ballot papers.

As I’ve written about this:

There’s the risk of ‘expressive polling’, where people give answers that best express their general outlook, rather than their actual view on the specific wording in front of them. If you’re very strongly pro-European and asked by a pollster if there should be another referendum, the best way of expressing your pro-Europeanism may be to say ‘yes’ even if, actually given the choice to make, you’d be not quite so keen on having one, at least right away. (It’s why when a politician is in a scandal, we sometimes get polling results claiming some people are as a result more likely to support them. They’re just picking the strongest way of expressing their support, rather than actually having becoming even more keen on them.)

It’s also a regular mistake of predictive punditry to take current trends and just extrapolate them into the future. Reality often changes course. Booms follow busts. Falls follow rises. Swings one way then swing the other way. In particular, there are many other issues, such as attitudes towards increasing public spending, where support rises and falls in waves in response to external events, the government’s record and the state of the economy.

So far, all we’ve seen is what happens during economic tough times under a Conservative government closely associated with Brexit. Indeed, the main turn against Brexit happened as the cost of living crisis really hit, so if it is in part a reaction to that, what will happen when, at some point in the future, the cost of living crisis has significantly eased?

Softness, especially when given details

That Redfield & Wilton graph shows a recent dip in support for rejoin, one that John Curtice has pointed out was replicated across other polls towards the end of last year.

There’s no certainty of a sustained, let alone growing, lead. As he put it:

It is far from certain that another referendum would produce a majority for re-joining. Despite widespread doubts about the benefits of Brexit, the anti-Brexit lead in the polls is not that large, differs between polling companies, and is far from invulnerable.

In fact, you can already see a majority for rejoin disappear when pollster questions give options other than simple rejoin/stay out. Take this Opinium question for example:

Thinking about Brexit, which of the following comes closest to your view?

36%: We should rejoin the EU

24%: We should remain outside the EU but negotiate a closer relationship with them than we have now

16%: We should remain outside the EU and keep the same relationship with the EU as we have now

14%: We should remain outside the EU and negotiate a more distant relationship with them than we have now

10%: Don’t know

The various stay out options add up to 54%, the one rejoin option is on 36%.

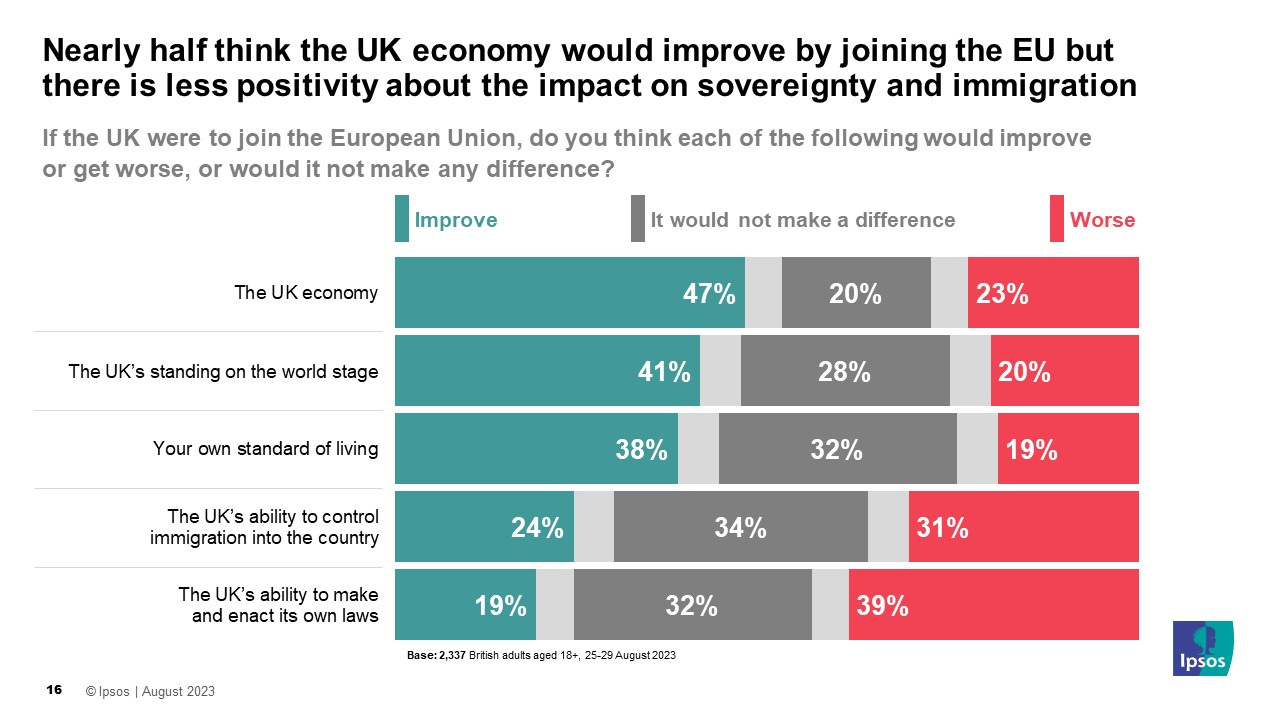

Another warning sign about the possible frailty of the rejoin lead is the breakdown of what people think rejoining would, or wouldn’t, improve. The areas that people think would get worse look very similar to what made for a winning Leave campaign in the referendum. That suggests a similar anti-EU campaign might once again win out:

Things also start to look different from a simple majority for rejoin when you dig into what a rejoin option might look like.

Take for example the WeThink tracker, which finds different answers when the Euro (membership of which is in theory, and possibly in practice, required for countries now joining the EU) is added in. A 52%-31% lead for rejoin in a hypothetical referendum becomes 42%-39% in favour of staying out when having to join the Euro is mentioned as a condition.

A reluctance to reopen Brexit

The third reason to doubt, or rather refine, the picture painted by hypothetical referendum polls is that even polls which show a rejoin lead in such a vote also show people not wanting such a vote.

To take the Redfield & Wilton tracker again as an example, that latest poll showing a lead for rejoin also shows a lead for saying that the UK’s non-membership of the EU is a settled question which should not be reopened:

Other pollsters have found a greater willingness to view the terms of Brexit as not settled. But that reluctance also plays out in two other important ways.

Both in opinion polls and in focus groups, people regularly say that they want to the government to focus on other issues, with Europe coming low down the list.

I covered in more detail last summer how pollsters ask about which issues matter most to voters, and in particular how Ipsos uses an open-ended question to which they can say anything in reply. That caters well for changing terminology such as people changing from using ‘Europe’ to ‘Brexit’ to ‘rejoin’.

So let’s turn to the Ipsos data first:

That puts Europe way down the list of issues for voters, and so far down that it doesn’t even make the top ten slide that Ipsos usually produces for its monthly data.

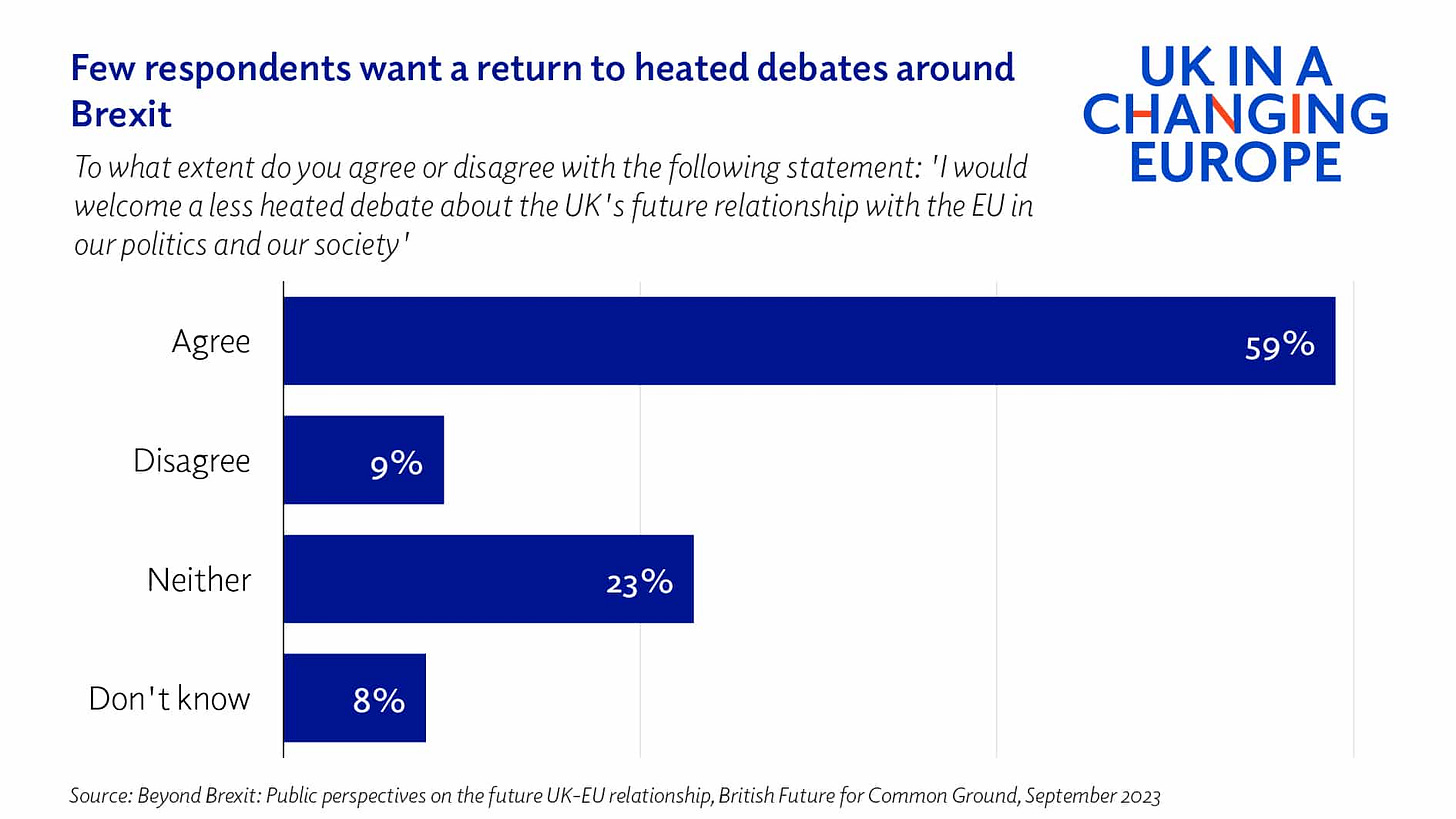

There is also a widespread dislike of the thought of a new round of heated debates over Europe:

Or to give an example from focus groups, here’s the take from focus grouper Luke Tyrl:

Talk to people in focus groups, even who think Brexit hasn’t worked, and the idea of years of further Brexit debates fills them with dread. Think a party reopening Brexit would quickly be on wrong side of public exhaustion.

Worth remembering people voted as much for the “done” as the Brexit part of “Get Brexit Done”.

That sort of reluctance is perhaps why a Deltapoll poll which had 51% saying they would vote to rejoin in a hypothetical referendum held today also found that only 43% thought that Britain rejoining the EU was the option they most wanted in the next 10-15 years.

Though we should also note that only 12% in that poll wanted the same, or more distant, relations with the EU. So there is plenty of support for warmer relations alongside the caution over what form they might take.

The impact on voting intention

So if there are reasons to doubt who might win a referendum in the near future, what about the impact on elections of being seen to be for or against changing Britain’s relations with the EU?

We have some data from the ballot box, courtesy of Rejoin EU whose name is its policy platform. It has had a series of extremely poor election results, both in several Parliamentary by-elections and the last London Assembly elections. It’s done consistently much worse than the Green Party when they’ve started pushing environmentalism up the agenda, or the days of Ukip’s growth and pushing of Euroscepticism. The verdict from voters has been clear.

Turing to the opinion polls, questions asking people whether if X happens they will change who they vote for needs handling with much caution, as they’ve often been of limited predictive power. In particular, by focusing people on just one topic, such polling questions tends to exaggerate the likely impact of that topic.

At best, therefore, such polling is indicative of the general direction in which voting support would move, knowing that actual movements may well be less than those the polling appears to find.

Yet even without that moderating caveat, the hypothetical voting impact data we do have doesn’t show a big electoral gain waiting to be harvested by a big pro-European push.

Here’s what UK in a Changing Europe found:

A Labour proposal to renegotiate the existing Brexit deal would make a fifth of voters (20%) less likely to vote for the party. 32% of those thinking of switching party after voting Conservative in 2019 say they would be less likely to vote Labour if the party proposed renegotiating the Brexit deal.

Our results in fact indicate that a pro-EU stance would increase merely support among those who already look sure to support Labour at the next election (for example, 60% of those who would be more likely to support Labour if they proposed a second referendum already intend to vote Labour at the next election). However, it might alienate a significant proportion of those yet to be convinced to vote for the Party.

Different polling by Deltapoll for the Labour Movement for Europe found results that the pollster’s client may not have welcomed. The poll found support individually for policies such as accepting EU standards on things like workers’ rights and on giving EU citizens the right to come and live here if they had a job lined up. But when asked if support for such policies would make people more or less likely to vote for a party, the poll only found a net +6 in support for Labour if Labour supported such policies, a net -12 for the Conservatives if they supported such policies and also a net -15 for the Liberal Democrats if they supported such policies.

So what does the public want?

It’s a very splintered landscape of preferences:

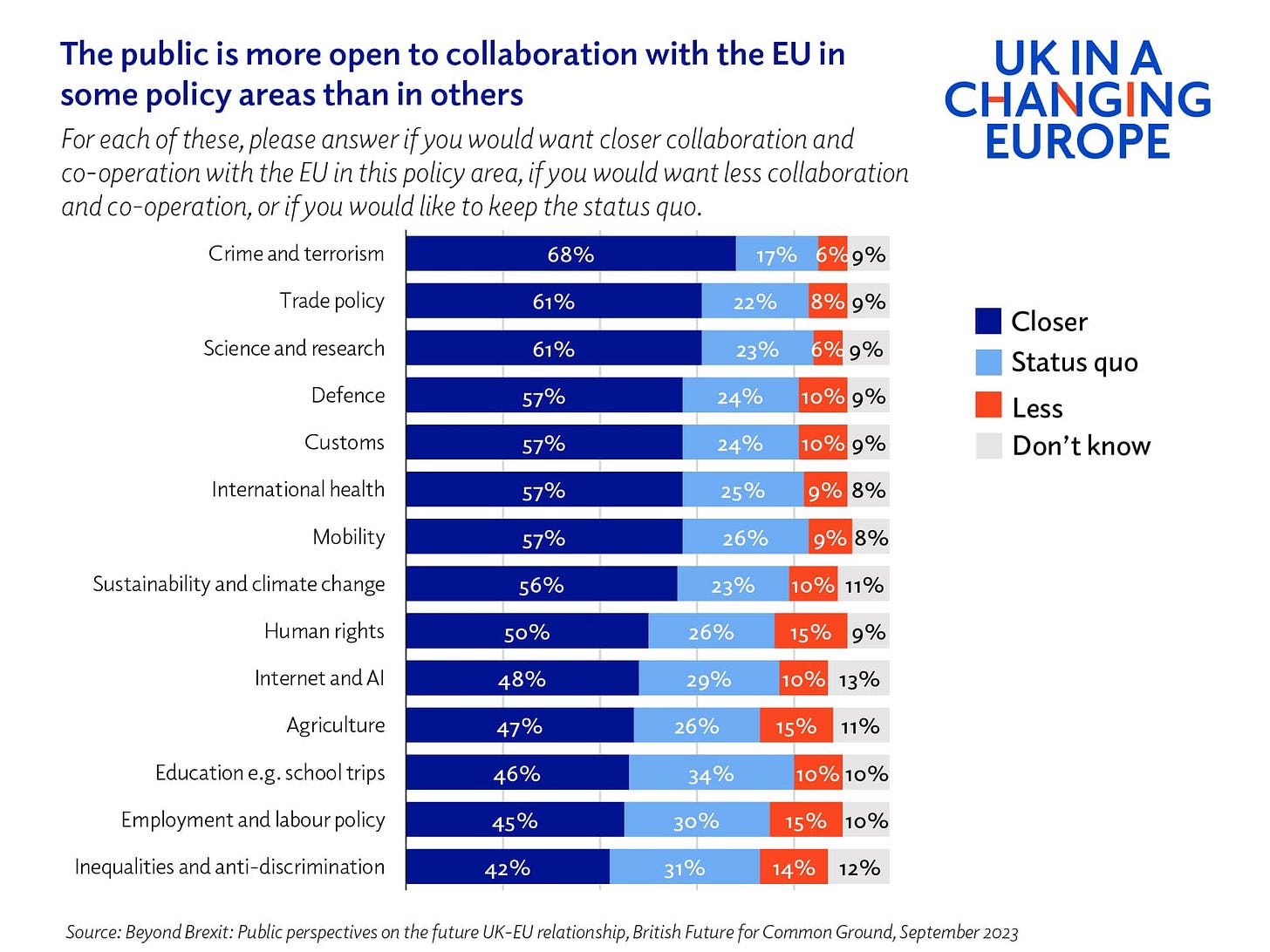

In a general sense people are happy to support closer and warmer relations with the European Union:

Some specific possible areas of closer relations get even stronger support:

Dig into questions about specifics, though, and it’s easy to find resistance. Take what might be expected to be fairly low hanging fruit for pro-Europeans: Britain having similar consumer good standards to the EU in order to make trade easier. Well this is what one poll found in this area:

Do you think that consumer goods sold in Britain should or should not be required to have a British rather than an EU safety certificate?

As many as 64% said that a British certificate should ‘definitely’ (28%) or ‘probably’ (36%) be required, while only 21% stated that it definitely (5%) or probably (16%) should not.

Moreover, a fabulous piece of cross-analysis by John Curtice compared people’s answers on whether the UK should have its own laws on good with their answers on whether the UK should adopt EU laws on goods. In a word of simple consistent answers, saying yes to the former should be followed by saying no to the latter, and vice-versa.

But reality is different:

While a majority of those who oppose adopting EU rules on goods also say the UK should have its own rules, as many as a half of those who say they support adopting EU rules also state that the UK should have its own rules. Overall, only 45% of respondents gave a substantively consistent response to the two questions.

The picture is much the same in respect of the other two pairs of items [polled]. Only 50% were substantively consistent in their responses to the propositions on the regulation of food, while just 38% gave consistent answers to the questions on the movement of persons – not least because in both cases a majority of those who supported the soft Brexit proposal also said they backed the equivalent hard Brexit one.

People saying they both want to adopt EU rules and yet also saying they want our own rules is a good example of how cross-pressured many voters feel. It’s like asking me if I’d to eat lots of chocolate and also if I’d like to eat healthily. Give me those as separate choices and I’ll say yes to both. Which is why asking me just one on its own isn’t that insightful.

Returning to Brexit, what this shows is that anyone touting a single poling insight - such as one polling question about, say, the single market or about the EFTA - is on unsafe ground. Public opinion contains multitudes that one question alone cannot capture.

In conclusion…

People do want warmer relations with the EU.

But they don’t want the issue to dominate politics. They want their politicians concentrating on other issues.

People often have doubts about specific moves to warmer relations and they’re unsure about reopening Britain’s membership of the EU.

Yet they’re unhappy enough about how Brexit is going as things stand that there is some scope to win support for improving relations with EU.

Even so, it’s not going to shift many votes in the near future and single-issue European candidate have bombed at the ballot box.

All that’s for now, of course, and things may change. The longer-term outlook certainly gives plenty of grounds for pro-Europeans to find hope. But the shorter-term outlook suggests they primarily need to look for votes via other issues.

More in the podcast…

It took decades of campaigning for Prohibition campaigners to win in the US, getting alcohol banned in the early twentieth century. Once they’d won, their victory seemed set to last. Yet in less than a decade and a half their victory had been undone and the the idea killed off politically. So can pro-Europeans take heart from drawing parallels between Prohibition and Brexit?

Find out in an edition of my podcast, Never Mind The Bar Charts, where I discussed just these parallels with Professor Ben Ansell, who delivered the Reith Lectures in 2023.

National voting intention polls

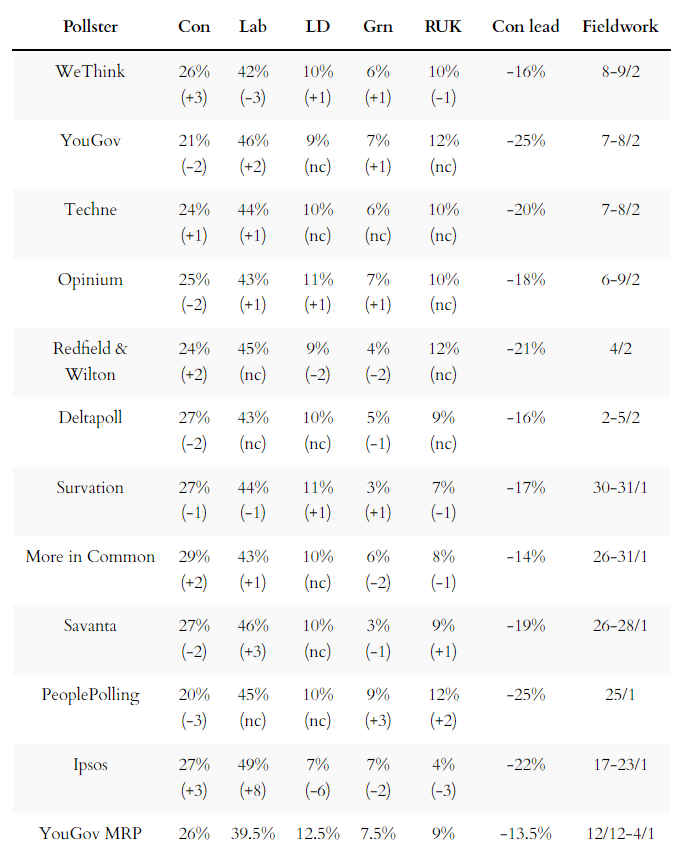

You know the drill by now about me saying how long it has been since the Conservatives were on more than 30% in the polls. So let’s go for some variation this time: Opinium, the pollster whose methodology is normally considered one of those most likely to generate better figures for the government, has the Conservatives on a lower vote share than Labour in 1983 and lower even than the Duke of Wellington in 1832.

Here are the latest figures from each currently active pollster:

For more details and updates through the week, see my daily updated table here and for all the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

A demographic bedrock of British politics has flipped, but will it flip back?

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

How question wording can raise (or reduce) Reform’s share in polls, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.