A demographic bedrock of British politics has flipped, but will it flip back?

Welcome to the 93rd edition of The Week in Polls, which returns to some eye-catching data on the changing demographics of voting in Britain and digs deeper into what’s going on.

Then it’s the usual look at the latest voting intention polls followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis. (If you’re a free subscriber, sign up for a free trial here to see what you’re missing.)

But first a quick round of applause for More in Common, who gave a detailed methodology briefing for their recent focus group work for the BBC. Although pollster transparency for polls is pretty good in this country (with some caveats as per last time), focus groups often get only minimal equivalent detail. Let’s hope this become more widespread, even though the British Polling Council has decided not to get into this area.

As ever, if you have any feedback or questions prompted by what follows, or spotted some other recent polling you’d like to see covered, just hit reply.

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

Already a reader and know others who might enjoy this newsletter? Refer a friend and you can get up to 6 months of free subscription to the paid-for version.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

The gender gap has flipped, but will it flip back?

In January I highlighted a big change in voting patterns that has gone mostly unremarked:

There’s been a big change in gender and voting

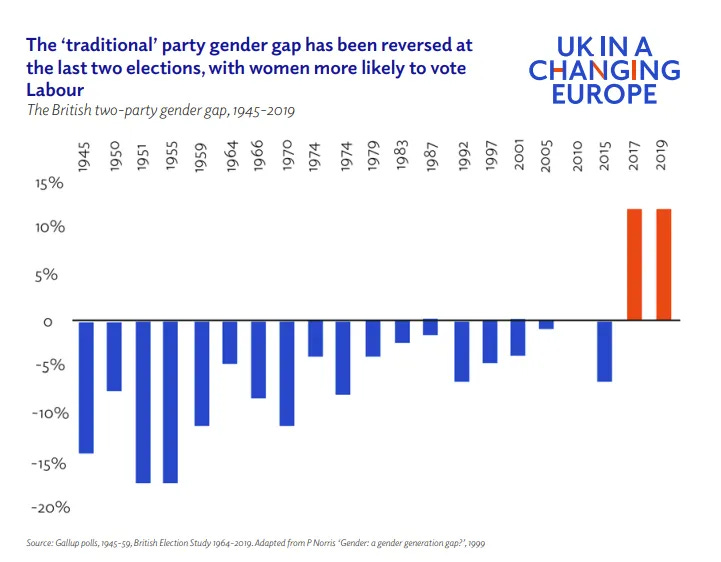

A seventy-plus years pattern now looks to be firmly broken and reversed. Although it does get mentioned, I don’t think the scale of mentions really measures up to the significance of what we’ve seen change in British politics (and where is the worry in the Conservative Party over this change?).

The FT’s John Burn-Murdoch has also highlighted a different gender gap, in this case one that’s opening up between younger women and younger men:

So what’s going on, and why? Academic Rosalind Shorrocks has handily summarised what political science can tell us.

First, there has been a significant generational shift from women being more right wing than men in older generations to being more left wing than men in younger generations:

Young women across Western Europe and Canada are more left wing than their male counterparts, according to new research [which] also shows among older voters women more likely to be right wing than men.

The research also showed that the gender gap in left-wing voting became larger for each new birth cohort. So, for example, the difference between women and men in left-wing voting was even greater for those born 1975-85 than it was for those born 1965-75.

In Britain that has translated to a change in voting patterns with the Labour-Conservative gender gap flipping.

But as she points out, that’s very context dependent:

The gender gaps in recent British elections can be linked to divergent reactions amongst younger voters to austerity and financial insecurity and Brexit.

Brexit in particular because as she adds:

[A] recent British Social Attitudes Report [shows] that there are actually very few areas of attitudinal divergence for younger generations in Britain - with attitudes towards Brexit an exception.

As that report says, it’s the case that:

The gender gap in voting seems more tied to changing events than changing values…

Our findings are in keeping with recent research that has shown that the salient political issues of the day, including attitudes towards Brexit and public services such as the NHS, and financial and economic concerns are more powerful explanations of the gender gap in party support than long-term values change.

In other words, with a different political environment, those generational changes might not have produced that voting flip - and so with different circumstances in future, it might flip back again. The chances of that in part depend on how likely and how far you think it is that austerity and Brexit are going to fade as issues.

This also explains the varying patterns across countries, as even where the value changes have been similar, events have not always been. Brexit in particular makes Britain stand out.

But, returning to those FT graphs, there are signs of something more happening amongst the youngest generations. I’ve covered before how they don’t seem to be getting more right wing as they age - which would be a seismic change in the basic bedrock of our politics if sustained.

Shorrocks adds more on that, including the research showing a rise in sexism among young men. This is part of the story in the widening gap between the views of younger men and younger women, although as those FT graphs show, there is still an overall liberalising trend with changes in a liberal direction for views on other social issues among younger men.

Tales of impending and sustained doom for a political party due to demographic change and other long-term trends often turn out to be hilariously wrong, decades later supplying secondhand bookshops with a range of anachronistically titled volumes their authors would rather you forgot.

That’s often not because the trends turn out wrong, but rather because parties and politics changes. Indeed one of the strengths of the Conservative Party in the UK has been its ability to repeatedly reinvent itself for new times.

So these trends do not mean it is doomed. They do, however, highlight how curious it is that - at least observed from the outside - so little of the debates in the Conservative Party over how to appeal to voters are over how to appeal to women, to young people or to Londoners.

Which is why my hunch is that the next Conservative Party leader to win power from opposition1 will do so by putting together a rather different voting coalition from the one the party’s current incarnation is trying to assemble to stay in power at the general election coming this year.2

For more on this topic, see Rosalind Shorrocks’s book, “Women, Men, and Elections - Policy Supply and Gendered Voting Behaviour in Western Democracies”, available from Amazon and Bookshop.org (which supports independent bookshops).

National voting intention polls

Yes, the run continues of polls putting the Conservatives on 30% or less. They were last over 30% in June 2023.

Here are the latest figures from each currently active pollster:

For more details and updates through the week, see my daily updated table here and for all the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

Some polling you should ignore: Telegraph/YouGov, round 2.

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Leavers are MORE critical of politicians who talk about ‘woke’ than Remainers, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.