Welcome to the 119th edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP) which starts with a return to a piece of mine from the start of last year. Do long-term trends mean doom for the Conservatives? That seems an even more apposite question now that we’ve also had the general election result.

Then it’s a summary of the latest national voting intention polls followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis. (If you’re a free subscriber, sign up for a free trial here to see what you’re missing.)

First though this week’s mild stare of disapproval goes to pretty much everyone involved in polling in the US for the habit of reporting polls in the form Jefferson 45% (+1), Adams 44%, using the +1 to indicate that 45% is one point higher than 44% rather than than the previous poll had Jefferson on 44%.

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

Do long-term trends mean doom for the Conservatives?

It’s always healthy to return to your previous analysis to see how good your prognostication skills really are. Plus it’s holiday season and so a good time to reuse words previously written. So here’s a post from January 2023, for which I have resisted using the advantage of hindsight to make edits other than very slight improvements to the language. But I’ve then added some new thoughts at the end.

The trends of doom

Two different experts have pointed to two different long-term trends that look very gloomy for the Conservative Party’s prospects.

First, academic turned pollster Patrick English, author of his own excellently-titled newsletter, Plain Speaking English. He tweeted:

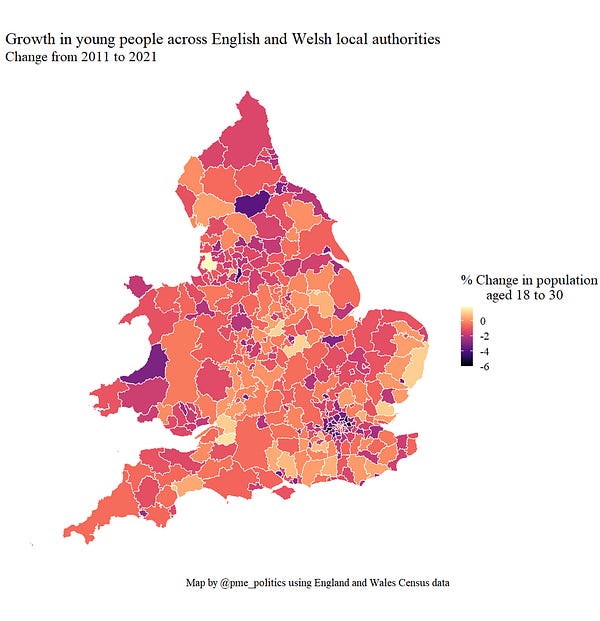

Patrick’s point is a variant of a trend that previously had its time in the chatterati-limelight, namely the way that very Labour urban areas, especially London, are ‘exporting’ non-Conservative voters to more Conservative areas thanks to internal migration.

Such moves may take the edge off enormous Labour majorities in some urban seats, but in return make Conservative seats elsewhere less safe. Such long-term increase in the efficiency of the distribution of the non-Conservative vote would not be good news for the Conservatives.

Especially as there’s more.

The Financial Times’s data wrangling expert John Burn-Murdoch has pointed out a very unusual pattern among Millennials in the UK (and the US). Unlike previous generations, they’re not getting more right wing as they get older:

So are the Conservatives doomed?

Well, not so fast… both pieces of analysis are good, and both seem to be based on solid data using sensible statistical analysis. Yet analysis of long-term trends that seem to point to doom for a particular party have often been wrong.

In the UK, for example, the excellent book Must Labour lose? was followed by Labour winning four of the next five general elections. Or the equally good Turning Japanese? about Conservative dominance was followed by Labour’s only-ever run of three general election wins in a row. Similar predictions of Conservative doom have proved equally faulty:

Three things go wrong with such predictions.

First, remorseless long-term demographic and social trends can add up to only relatively small numbers per constituency changing (a point that Patrick acknowledges in his full Twitter thread). That matters at the margins in a close election, but matters much less for a party’s political prospects than whether it has as its leader Harold Wilson or Liz Truss.

Second, political shocks and other trends come along too. The future of British politics isn’t only going to be determined by age profiles and one generation. Just as Butler and Stokes were both right in that 1969 piece but also wrong in missing the other trends that worked against Labour.

Third, political parties are not - despite appearances at times - run by complete dolts.1 They can see an electoral problem and react to it.

The British Conservative Party has show a remarkable ability to reinvent itself. As a result, it has won two of three elections since the Second World War. If long term trends are changing our politics, perhaps the party that has shown the most flexibility to move with the times is the one that should be favoured, not written off?

Both the second and third of those points explain the paradox at the heart of the excellent book Brexitland. I’d peg it as the best book on the trends shaping our politics. And yet it paints a picture of an increasingly liberal society at a time when the non-liberals have been on rather an election and referendum winning roll. (The answer to that paradox lies, in my view, in the two-speed liberalisation of Britain, something I wrote about here and discussed on my podcast with one of the co-authors, Rob Ford. For more on this, see also this previous edition of The Week in Polls.)

So no, the Conservatives aren’t doomed.

Those trends mentioned above will help the opposition parties at the next general election, but they won’t hand victory on a plate to anyone.

How does this all read now, after a general election in which the Conservatives did even worse than they did under the Duke of Wellington in 1832? The analysis from both Patrick English and John Burn-Murdoch stands up pretty well, though note that there is not a simple match-up between the places with the biggest age shift in Patrick’s graph and the places where the Conservatives lost seats in the general election.2

As for what the trends mean for the future of the Conservatives, I think this other earlier analysis also holds up well:

Tales of impending and sustained doom for a political party due to demographic change and other long-term trends often turn out to be hilariously wrong, decades later supplying secondhand bookshops with a range of anachronistically titled volumes their authors would rather you forgot.

That’s often not because the trends turn out wrong, but rather because parties and politics changes. Indeed one of the strengths of the Conservative Party in the UK has been its ability to repeatedly reinvent itself for new times.

So these trends do not mean it is doomed. They do, however, highlight how curious it is that - at least observed from the outside - so little of the debates in the Conservative Party over how to appeal to voters are over how to appeal to women, to young people or to Londoners.

Which is why my hunch is that the next Conservative Party leader to win power from opposition will do so by putting together a rather different voting coalition from the one the party [targeted in the 2024 general election].

National voting intention polls

A thin table so far I’ve reset it to include only post-general election polls:

For more details and updates through the week, see my daily updated table here and for all the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

What do the post-election polls tell us so far?

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Debate over how the polls did at the general election, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.