Welcome to the 152nd edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP) which, after last week’s dive into technical polling details, this time has some polling-adjacent figures for the more general reader, a look at what happens to parties with large numbers of MPs.

Then it is a summary of the latest national voting intention polls and a round-up of party leader ratings, followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis.

This time, those ten include data showing how deeply split Reform voters are over whether their party would do better with or without Nigel Farage.

If you are not yet a paid-for subscriber, you can sign up for a free trial now to read that and all the other stories:

Before we get to all that, a quick note about the Electoral Calculus poll-based predictions just out for seat gains and losses at the May local elections. More data and polling about local elections is always welcome, though it’s only reasonable to highlight how hit and miss the track record is for these seat predictions:

And with that, on with the show.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

What happens the election after a landslide?

Big majority equals government that will last for a long time.

That seems an obvious, banal statement to make. It is certainly the assumption that underpins a lot of political commentary, such as in the immediate wake of Boris Johnson’s 2019 election win or Keir Starmer’s own last year. It is an assumption that I have made myself.

But thinking about it recently… I started to wonder. Because my own assumption perhaps comes from being of an age where my formative experiences were the 1983 and 1997 landslides, one each for Conservative and Labour and both seeing the large majority then decline away over several Parliaments. Landslides seem to bequeath long-term government.

But is that really a feature of reality or just a quirk of when my formative experiences were, setting the expectations for ‘normal’? Especially as apparent political dominance can be a fragile thing:

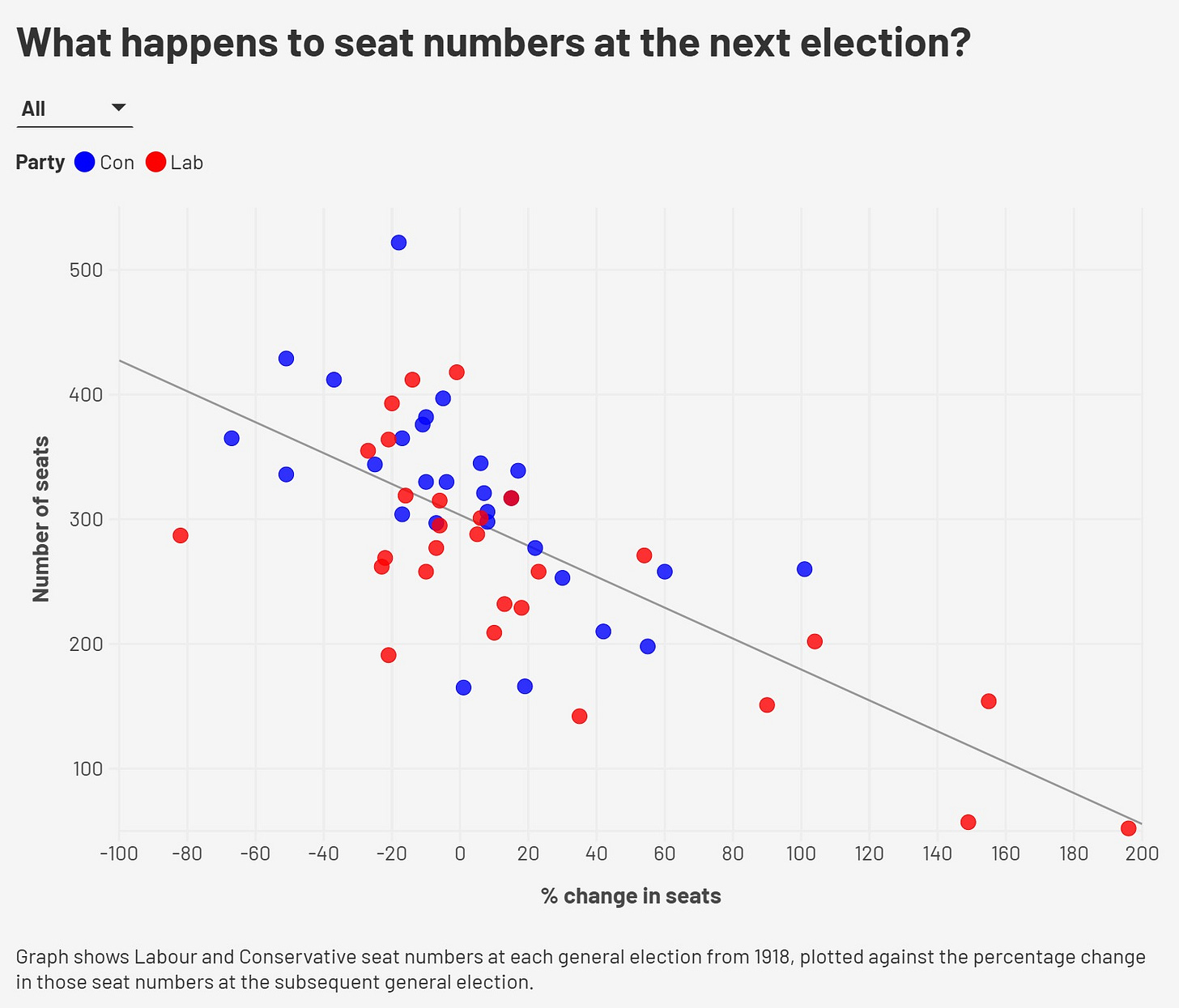

Here then is the data comparing the number of MPs won by Labour or the Conservatives at each general election since and including 1918 with the percentage change in the number of MPs for that party at the subsequent general election.1

(I have omitted the Liberal Democrats because the combination of 11 seats in 2019 and 555% growth at the next election makes for an absurd outlier that squashes up all the rest of the history into a small space.)

Down in the bottom right, for example, we have Labour’s 1931-35 experience, where 52 MPs in 1931 became 154 in 1935, a growth of 196%.

There is a clear trend line here, one that shows the weaknesses in those assumptions about landslides lasting. Rather, reversion to the mean is a better rule of thumb.

In other words, on average, the more MPs a party wins at an election, the larger the percentage share of them it loses at the next contest.

With Labour currently on 412 MPs, this suggests that - on average, if history continues to repeat itself - it would be on course for losing a large percentage of its seats next time.

However, the plausible margin of variation around that is large. On seven previous occasions a party has won within 30 seats either way of Labour’s 2024 tally.2 The subsequent change in MP numbers for that party has been -51%, -37%, -20%, -14%, -10%, -5% and -1%.3

This averages -20%, which, if applied this time around, would give Labour at the next general election 330 seats, a very small majority.

But, but, but… this is based on history, on data with a lot of noise and on averaging a set of numbers with a large spread in them.

Even so, it is fair to draw the conclusion that big seat hauls are often followed by a sharp fall back to earth.

Dominance is a brittle thing.

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

Here are the latest national general election voting intention polls, sorted by fieldwork dates:

Next, a summary of the latest leadership ratings, sorted by name of pollster. Ed Davey continues generally to have the best net scores, and Keir Starmer seems to be having a bit of a Ukraine-related bump:

For more details, and updates during the week as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Catch-up: the previous two editions

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. For content from YouGov the copyright information is: “YouGov Plc, 2018, © All rights reserved”.4

Quotes from people’s social media messages sometimes include small edits for punctuation and other clarity.

Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Reform voters evenly split over whether they would do better without Nigel Farage, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Reform voters from 2024 split almost exactly equally (33%-34%) on whether their

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.