Welcome to the 151st edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP) which takes a look at a new(-ish) book about both the problems with and possible solutions for modern political polling.

Then it is a summary of the latest national voting intention polls and a round-up of party leader ratings, followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis.

This time, those ten include how Reform’s new supporters since the 2024 general election differ from their supporters at the general election.

If you are not yet a paid-for subscriber, you can sign up for a free trial now to read that and all the other stories:

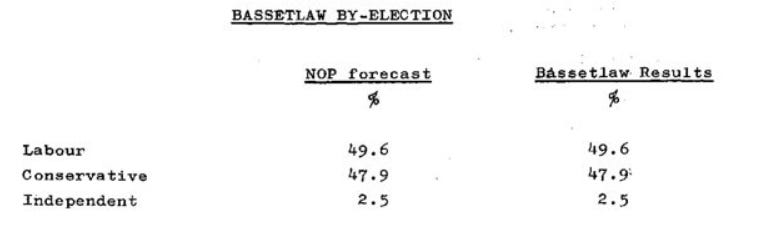

Before we get to all that, a strong entry for the best piece of political polling ever, found in the 1960s NOP archives that I am currently working through. It was for the 1968 Bassetlaw Parliamentary by-election:

And with that, on with the show.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

Polling at a Crossroads by Michael A. Bailey

Published last year, Michael Bailey’s book, Polling at a Crossroads: Rethinking Modern Survey Research, clearly sets out how modern political opinion polling has diverged from the would-be theoretical purity of random sampling.

The theory and maths of much of modern polling derives from the ideal of sampling a genuinely random selection of people. In practice, however, those who are polled are not purely random. If nothing else, those unwilling to take part in polls are under-represented in the samples of pollsters. But other factors apply too, such as how likely someone is to be found by a pollster. In the heyday of telephone polling in the UK, for example, even calling a random set of phone numbers would usually get a sample skewed towards Labour due to who was reachable on the phone and willing to do a survey. Response - and hence also non-response - rates to polls are not evenly distributed, but rather some parts of the public have higher non-response rates than others.

Part of the solution to this is - for those polls with bigger budgets and time to spare - to try really hard to get hold of people and to persuade them to take part in a poll. ‘Gold standard’ social science type surveys often involve calling back on people multiple times to try to get them to take part.

Even this though does not restore the purity of random sampling, and is not an option for the budgets and timescales available for most polling. Therefore weighting has also been developed as a technique. Get more women than men answering your survey, for example? Weight the answers to bring them into line.

Bailey’s book neatly sets out the strengths and limitations of weighting and introduces the counter-intuitively named (not by him, to be fair) concepts of ignorable and non-ignorable non-response.

Ignorable non-response should not be ignored. Rather, ignorable non-response is the sort of problem that weighting can fix.

To take that example of a pollster getting more women than men answering their survey, this is an ignorable non-response problem in that you can find out what the women/men balance is in your answers, check against authoritative population data to see what the balance should be and weight your figures accordingly. It is, in other words, a problem that can be ignored in that it can be adjusted for.

(Quota sampling - specifying how many men and women you are going to ask - is another technique for addressing ignorable non-response in polling. Pollsters however generally moved on from primarily using quotas to primarily using weighting, for reasons the book explains well.)

These sorts of adjustments have served pollsters more than adequately over the decades, though Bailey also provides a very clear example of how quotas and weighting can sometimes make results less accurate.

He also highlights the problem with using one set of weights across a whole poll, when theory points towards creating your weights separately for each question. The former may be pragmatically more practical, and hence widespread, but that does not make it theoretically rigorous.

Despite their limitations, quotas and, especially, weighting are helpful tools, which have assisted political polls in generally performing well.1 But they have not been perfect. Moreover, that may well be becoming more of a problem as pollsters move more and more away from any sense of randomness in their sampling, such as due to the increasing reliance on internet panels and the decline in response rates for telephone polling.

Therefore non-ignorable non-response is likely to be on the rise as a problem, and it is a tougher nut. Here, your sample is biased in a way in which you cannot measure and/or cannot adjust for as you can for ignorable non-response. For example, you may know that it is likely your sample is biased towards those who like taking part in polls. But how do you measure that precisely among not only your poll respondents but also the population as a whole, so that you can weight for this?

More practically, this means you have a problem if there is - say - a political candidate who regularly trashes the reliability of polls, and so may be putting their supporters off taking part in polls. That may well result in skewed samples but you cannot measure this in a way that lets weighting fix things.

This may seem to leave pollsters at an impasse, but the more technical latter parts of the book set out how recent statistical developments have started to provide tools to get to grips with some of the issues of non-ignorable non-response. The crux of this is that:

While it is true that non-ignorable non-response depends on the correlation of unobserved variables [e.g. willingness to take part in a survey being correlated with voting choice], it is not true that non-ignorable non-response leaves no trace. When non-response is non-ignorable, survey averages will vary as response rates vary; when non-response is ignorable, survey averages will not change as response rates vary.

So, for example, you can compare the results from those who are quickest to respond to a request to take part in a poll with the results from those who you have to repeatedly pester before they respond. If you get different answers from each set, that shows non-ignorable non-response is at work - and so gives you some data for clever statistics to work on.

A new road for polling, Bailey therefore argues, is to develop methodologies that generate multiple different scenarios such as ‘quick to respond to survey request via email’ versus ‘slow to respond to survey request via email’ and then employ recently developed statistical approaches to spot if there is likely to be much in the way of non-ignorable non-response going on, and if so to model your way past that.

That maths is beyond my abilities to evaluate properly, though I came across the book due to James Kanagasooriam’s praise for it - a good sign that the maths does hold up. And even if you end up skimming past the more technical parts of the book, there are regular returns to short, plain English explanations - and even a fairy tale analogy.

The book does not offer one magic bullet solution for the problems it sets out, but it sets a direction and along the way helps us understand better the strengths and weaknesses of the non-random, weighted polls that dominate political polling.

You can get Polling at a Crossroads: Rethinking Modern Survey Research by Michael A. Bailey from Amazon, Bookshop.org or Waterstones.

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

Here are the latest national general election voting intention polls, sorted by fieldwork dates:

Next, a summary of the latest leadership ratings, sorted by name of pollster. Ed Davey continues generally to have the best net scores, and Keir Starmer seems to be having a bit of a Ukraine-related bump:

For more details, and updates during the week as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Catch-up: the previous two editions

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. For content from YouGov the copyright information is: “YouGov Plc, 2018, © All rights reserved”.2

Quotes from people’s social media messages sometimes include small edits for punctuation and other clarity.

Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Who can best beat Reform?, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

YouGov has asked voters who they would pick in a series of hypothetical match-

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.