Welcome to the 169th edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP) which starts with both a correction and a clarification related to my analysis last week about where Labour’s 2024 support has gone.

The correction comes with thanks to reader Bruce, who pointed out that the Ipsos figures in my table added up to an implausible 107%. Thankfully the error did not alter the ratios between switchers to the liberal/left and to the populist/right, and so the rest of the analysis stands. I have updated the table and last week’s edition with the correct numbers. (In my weak defence, the error came from Ipsos putting out crosstabs where the percentages in the column I used also added up to 107%.)1

The clarification comes from a story in the New Statesman. Its 4 July edition has (on p.14) a graph showing where Labour’s vote has gone since the general election and sourced to “Stack Data Strategy”. The reason I did not include any data from Stack in my own analysis is that… there isn’t any such polling from them. Thank you to Stack for confirming this promptly when I checked with them. Rather, that graph was based on collated public polling from others.

This week, it is a dive back into the history books. Earlier this year readers liked my piece about Neville Chamberlain’s poll ratings. So this time I am taking a look at those of Winston Churchill during the Second World War, which have always puzzled me for two reasons. See if you can crack the puzzles.

Next comes a summary of the latest national voting intention polls, seat numbers from the latest MRPs and a round-up of party leader ratings.

Those are followed by, for paying subscribers, 10 insights from the latest polling and analysis.

This time, those ten include data on who is open to voting for a new Jeremy Corbyn-led party.

Finally, a reminder that if you are interested in understanding polling better, or fancy a tour around some of its weird corners and intriguing history, then I have a book about it all: Polling UnPacked.

And with that, on with the show.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

Podcast: where has the Labour vote gone?

Just before calculating the figures for last week’s piece, I recorded a podcast with ace polling analyst Steve Akehurst, whose work has often featured in this newsletter. Indeed, it was Steve’s comments that prompted me to get around to crunching the numbers. Here’s what we discussed:

Two puzzles about Winston Churchill’s poll ratings during the war

The calendar has rolled around for it to be time for another update to my Pollbase data set of voting intention and approval ratings polls from 1938 up till the end of Quarter 2, 2025.

In addition to another quarter’s worth of polls, this update includes:

Additional Stack Data Strategy polling from the 2019 and 2024 Parliaments.

Additional Gallup data from pre-1945 and from the 1945, 1950, 1951 and 1955 Parliaments.

Additional and corrected data for some MORI polls from the 1974 Parliament.

Additional NOP data from the October 1974, 1979, 1983 and 1987 Parliaments.

Additional Parliamentary by-election polls from the 1980s.

A small number of other polls from the 1983 Parliament and also one from the 2019 Parliament.

As I have, for the moment, exhausted sources of additional data for pre-1945 polls, now is therefore a good time to turn to Winston Churchill’s polling during the Second World War.

Courtesy of Gallup, we have regular polling both on the public’s approval ratings for Churchill and also on the public’s satisfaction levels with how the government was conducting the war.

Let us start with a graph showing just the government’s ratings:

As the graph shows, the government’s ratings generally got better as the war progressed and from 1943 onwards were consistently very positive.

The big fluctuations early on correspond to high profile events that dominated media coverage of the war. In early 1942, the fall of Singapore (and perhaps also the Channel Dash, militarily of little significance but hugely embarrassing) sees the government’s ratings take a big hit.

The fall of Tobruk later in the year has the same impact. (The military impact of the fall of Tobruk is debatable, even within the context of the North African campaign alone, let alone if put in the wider context of how much the course of the war in the Mediterranean mattered or the even wider context of whether or not any battles mattered that much compared with the economic production race. But I’ll leave all that to the likes of Richard Overy and Phillips O'Brien to argue over and simply note that in the public reporting of the war, and in the private reactions of senior figures, it was seen as a major humiliation.)

If you knew that there was a vote of censure in the House of Commons “in the central direction of the war” but did not know its date, you would be able to guess it accurately using the graph, for it was in early July 1942. The government won, by 475-25.

You can also spot the Battle of the Bulge, with its initial knock to the government’s ratings.

What you might struggle to locate on the graph, however, is when D-Day occurred. The blip upwards in the government’s ratings in late 1944 may tempt you… but that was the time of the liberation of Paris and the rapid Allied advance across France. D-Day itself, in early June 1944, gives a bit of a bump to the ratings. But it is not a great bump, and the June-August ratings overall are only slightly better than the average through 1943.

What then about Winston Churchill’s ratings?

Here is the graph with his ratings added (also online in an interactive version here):

For Churchill, we see a much flatter picture. His approval ratings are consistently high, with much less variation than those for the government. There is a bit of a dip around military disasters or shocks. But the variations are small and there is even less of a D-Day bump for him.

Therefore, while Neville Chamberlain’s ratings told us a story in which the polls and external events lined up neatly, we are left with two puzzles over Churchill’s ratings.

The first is that, for all that the conduct of the war was seen as being so personalised around him, his own poll ratings were much more immune to the changing state of the war than the government’s.

Churchill was seen as the undoubted head of Britain’s war effort, and yet when the war effort went badly, it was the government’s standing, but not his, which mostly suffered.

This is perhaps an extension of the pattern that saw him become Prime Minister in the first place. Churchill was the prime instigator of the disastrous invasion of Norway. Its failure brought down Chamberlain as PM and… saw the mastermind of the failure become Prime Minister instead.

The second is that D-Day was a hugely heralded event. The opening of a Second Front had been a high profile matter of debate, and obvious importance for several years prior to it. It was a very obvious success, in that troops crossed the Channel and managed to stay there. It certainly helped deliver on what the public overwhelmingly wanted: a military victory to bring the war in Europe to an end. Yet the polls barely budged.

Curious.

A little bit of polling trivia to end with. In March 1940, while Neville Chamberlain was still Prime Minister, Gallup asked people who they would most like to see in a smaller war cabinet, if one was formed. Churchill and Anthony Eden were the two most popular picks, with Chamberlain tied fourth with Lord Halifax.

But who came third?

Answer next time. Or flaunt your knowledge by emailing me your answer now…

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

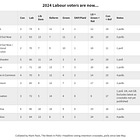

Here are the latest national voting intention figures from each of the pollsters currently active, and perhaps the most notable feature of the table is what everyone has got used to seeing: the Conservatives in third place, frequently under 20%.

Next, the latest seat projections from MRP models and similar, also sorted by fieldwork dates. As these are infrequent, note how old some of the ‘latest’ data is. Note also how close the Conservative Party is to falling to fourth or even, with some models, fifth (!) on seats.

Finally, a summary of the latest leadership ratings, sorted by name of pollster. As with Reform’s voting intention scores, Nigel Farage’s ratings rose in the month after the local elections and then have plateaued.

For more details, and updates during the week as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Catch-up: the previous two editions

My privacy policy and other legal information are available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. For content from YouGov the copyright information is: “YouGov Plc, 2018, © All rights reserved”.2

Quotes from social media messages are sometimes lightly edited for punctuation and clarity.

If you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, please note that unsubscribing from this one won’t automatically remove you from the others. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Greens most at risk from a Corbyn-led party, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Although a Jeremy Corbyn-led new political party would be one born out of splits in the Labour Party, it is the Green Party’s support that would be most at risk if

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.