Welcome to the 144th edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP), which contains a special long read on what a process of relentless incrementalism to improve the self-regulation of political polling in this country could look like.

Occasional calls for big bang reform, such as the - in my view mistaken - calls for polls to be banned, are what usually get attention. But I think there is a lot of mileage in a programme of many small improvements, none expensive and none requiring major work. Read on to see what you think, and do let me know your thoughts.

Then it is a summary of the latest national voting intention polls and a round-up of party leader ratings, followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis.

This week, that includes more data showing the British public’s increasing hostility to Elon Musk.

Before we get down to the contemporary polling business a follow up to my previous snippet of NOP polling from 1963 showing big public approval for the idea that “a large proportion of the railway network must be closed” following Dr. Beeching’s notorious report. That prompted several readers to ask about how the transport minister fared in polling at the time. Here is how he did in the following month’s NOP poll:

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

An accumulation of modest proposals: how to improve political polling’s self-regulation

The British Polling Council

For a sector that generates so much news coverage and gets such attention from politicians, not to mention the periodic bursts of dismissiveness about whether its figures are right or relevant, the political polling sector in the UK is lightly regulated.

Some pollsters are members of the Market Research Society (MRS). All have to pay due deference to data protection laws, particularly GDPR. But the only initials that really cover political polling are those of the British Polling Council (BPC), the sector’s self-regulatory and light touch body.

Its fees are low, its obligations are light and its remit is narrow. Even a global multinational with a multibillion turnover needs pay just £750 to join and £200 a year subsequently.

It is only a slight condensation of the already brief BPC rules to say that what they require of political pollsters is to disclose certain basic facts about any of their polls which get public circulation. It is a narrow, focused set of rules.

Despite, or perhaps because of, that narrow remit, the system has worked pretty well over the years. The transparency levels about exact question wording and crosstabs may be light, but the rules have been effective on their own terms.

The standards of transparency that we see in the UK are by no means global. Australian pollsters (at least until recently, as things are changing) appear bizarrely secretive to British eyes for example, with some even withholding basic details of their polls from an industry inquiry into a polling miss. Or there is the bearpit of US polling, where accusations of fake poll results are not the preserve of conspiracy theorists but a necessary concern of any assiduous polling analyst.

Even the most controversial UK pollster of the last Parliament - PeoplePolling - diligently put online the information required under BPC rules. (It is also a polling firm that, judging by Company House, will shortly cease to be.) Lord Ashcroft is not a member of the BPC, but his polling is published in line with the BPC’s rules save for the wording about historical margins of error.

Running further back through the decades, other controversial pollsters of their time have likewise abided by the rules with perhaps just the one exception, that of BPIX. It was always curiously silent about basics of its polls, but it was a rare exception of a pollster whose voting intention figures appeared in the national media but who was not a member of the BPC. Although its polling results were therefore shrouded in a degree of obscurity, there was never any suggestion that the results were not coming from properly conducted polls. The word on the street, as it were, was that the obscurity came from a genial failure to get around to sorting out the administration rather than anything nefarious.

All in all, pretty small beer as far as polling ‘scandals’ go. Add to that the polls generally doing a pretty good job, and you can see why the polling industry’s regulation has topped out at such a light touch level.

But what might a different regulatory environment look like? What if a polling miss or polling scandal triggered a need for the industry to up its game? Or what if wise heads decided to pre-empt such a risk and up the regulatory game without waiting for disaster to come first?

Even leaving aside the drastic (and in my view, completely wrong) idea of banning polls in the run up to an election, there is much that could change.

As the industry is not in crisis, and outside forces are not marshalling at the door to demand change, let us look at what modest reform would look like. As we will see, there are quite a few small, cautious, moderate steps, which together would add up both to a much improved regulatory framework and one, frankly, that would be pretty easy to get to. No large costs involved. No business models having to change. No onerous new paperwork. No increase in the BPC fees required and only a few paragraphs at most to add to its rules.

Think that sounds too good to be true? Well, let me show you.

Tweaking the transparency rules

The first step would be tighten up on compliance with the existing rules.

The core transparency rule of the BPC is clear:

2.3 … The public opinion polling organisation responsible for conducting the social or political poll that has entered the public domain will place the following information on its own web site within 2 working days of the data being published.

Now, such information does end up being released. But always within 2 working days? If only.

A regular weekend experience of mine, while catching up on data for my polling records, is to find that data tables for a poll have not yet appeared. When I then ping an email off to someone at the relevant polling company, the responses have nearly always been so prompt that if anything the worry should be about work/life balance in those firms with replies and even data being sent before the weekend is out. Matt Goodwin included, all pollsters I have found respond pretty quickly and well.

Sometimes it takes a few emails, and just occasionally it required a Deploy The Curtice email to then BPC President, Professor Sir John Curtice, to chivvy them along. (I am sure pollsters would be just as responsive to his successor, Professor Jane Green, but I have not yet had a need to resort to asking for her intervention.) In one long-running saga, I know some staff illness was involved, and in all cases, the data appeared and there is no reason to suspect anything dodgy going on.

But… it is all a bit sloppy. The 2 days deadline is not being followed with the zealousness with which many other sectors of the economy follow their own regulatory deadlines.

Moreover, there has been a new pattern in recent years of pollsters slipping out polling data via graphs which contain older data points that never had data tables published at the time. It has become a fun side-hobby to look at a pollster’s new graph to spot the new old polls. Again, every time I have contacted a pollster about a graph ‘revealing’ an old data point without public data tables, the data tables have then been made public.

So again, not nefarious. But also, not super-hot compliance and it is a repeated experience of mine to find data tables taking a few weeks rather than 2 days.

The most modest of improved self-regulatory steps would be to properly implement the 2 working day rule.

Catching up with the news cycle

But 2 working days? Is that really good enough, given how quickly the news cycle and attention spans move on? It means that if, say, a Sunday newspaper publishes a poll, and so people start talking about it on social media on a Saturday evening, the transparency rules do not require the data to appear until the end of the working day on Tuesday. The caravan will have moved on and the stories about the poll be firmly set in everyone’s minds long before transparency has to arrive.

Again, to be fair to pollsters, many are better than this, most of the time. In fact, the current Saturday evening polling regular, Opinium, puts out social media messages with its tables that evening, ahead of the print version of the newspaper with the poll appearing.1

Many and most, though, is not as everyone and always. Why not cut those 2 days to a shorter time span?

But even that is still modest. Why not require simultaneous release of the data?

This is not just a theoretical issue. Look at how badly managed this recent Sunday newspaper front page was, the headline not reflecting the poll and the story not anywhere mentioning that, compared with the previous poll from the same pollster, it showed Labour’s lead up. A different editorial line could have led to very different, completely accurate, headlines. If publishing data tables is meant to achieve something, then when events like this occur, they should be immediately available.

That is after all the norm with many other statistics that inform news stories. You do not see headlines about the rate of unemployment and then have to wait up to 2 working days for the data. The full data is out there as part of the story.

It is a little trickier for pollsters as many of their polls are for media clients or others, rather than being self-published. Their clients may mess pollsters around over when a story is going to be published or may change their plans. Yet pollsters have generally done a pretty good job persuading their media clients to include appropriate disclaimer text about the timing and accuracy of polls.

So it only requires a little ambition - and perhaps a little bit of work with the media regulators - to move to a world where the polling data appears at the same time as the polling story.

(And who knows, media clients may turn out to quite like this. After all, they are currently in the slightly bizarre situation of frequently paying for lots of polling detail that they not only do not put in their story but also, despite years of talk about data journalism, leave unpublished and unlinked all that extra data. The media outlets pay for data and then require those wanting to see all the data to go to the pollster rather than coming to themselves to find it. Whether from a desire for more data journalism or more website traffic, including the data with their stories has upsides for the media.)

Expanding the transparency rules

Polling context

All of this, however, is taken as given the existing remit of what transparency there has to be, encapsulated in the polling crosstabs that pollsters publish.

There is, however, important information missing from those crosstabs.

First, the crosstabs show us the questions that were asked and in what order, but do not tell us what other questions may have been asked before or even whether any such questions were asked. For a ‘full’ political poll, usually there will be no such other questions. But pollsters also regularly drop questions into their ‘omnibus’ poll, that is a poll made up of disparate questions, perhaps paid for by different clients.

We simply have to take on trust that the pollster has not put other questions in first which end up biasing the answers to subsequent questions due to the framing effect. Pick the right earlier questions and you can influence the later answers, as Yes Minister memorably demonstrated.

If other questions were paid for by other clients, possibly nothing to do with politics and wanting the polling for internal reasons, there are good reasons why those other clients may reasonably wish for their questions to be kept confidential.

We simply do not know how much of an issue biasing previous questions are. It is plausible that they are the occasional explanation for an odd polling result. It is plausible too that no-one knows how much of an issue it is, because any pollster who makes such a mistake, even if they notice it, is unlikely to want to broadcast it to everyone. Even though they will know of their own mistake, they will not know how widespread such mistakes are among other pollsters.

However, there is no need to trust that public silence reflects the absence of a problem rather than embarrassed silence over a problem.

A - slightly - tougher regulatory environment would require a pollster either to state that no other questions were asked before those published, or to reveal that others were and, at the least, publicly commit that to the best of their professional knowledge, they were not questions that would have influenced the result, with a commitment to make the full set of questions available to the BPC for inspection in case of doubt.

Panel transparency

Nearly all political polling in the UK is now done online, generally, though not exclusively, using panel data. That is, someone has put together a database of people willing to take part in polls and some of them are messaged, inviting them to take part in the poll.

Some pollsters have their own panel. Other pollsters buy in to access someone else’s panel. And other pollsters use a mix of panel data from different sources.

There is skill - and hence commercial advantage - in picking the right mix of panel data to use. Especially as in addition to traditional panel data, pollsters also increasingly use ‘river sampling’ where they proactively place their polling questions online in front of people, to get to a more diverse sample.

So some degree of secrecy over exactly what each online pollster is doing is understandable. It is, though, also problematic as it means no-one - including pollsters themselves - know quite how independent different polls are from each other.

If both polling firm X and Y use the same panel data, then their results are not as independent from each other as may appear. If X and Y are getting different results from Z, is that due to Z doing something different, or due to the (secret) shared panel data between X and Y?

The food industry is well used to tackling this problem, that is having key players who want to keep secret quite what they put in their products, while also having a strong reason for public transparency. We both have rules requiring transparency over ingredients and also Coca-Cola keeping secret its exact formula, or KFC keeping secret its exact list of herbs and spices.

If the food industry can manage it, then surely the polling industry can do better than simple silence?

It could become a simple BPC requirement for pollsters to list their panel suppliers and what proportion of their overall sample came from each. That would still leave plenty about exactly how each panel supplier’s data was specified and used, and so retaining - Coca-Cola and KFC like - their commercial secrecy and hence, if they are any good, their competitive advantage.

Tackling the crosstab conundrum

If I was meaner, I would call it the crosstab hypocrisy. But instead I will explain the conundrum with the assistance of some chocolate.

Imagine a parent with three children. The parent places a huge bowl full of Maltesers2 on the kitchen table and sternly tells the children they must not, under any circumstances, take even one single Malteser from the bowl while the parent pops out for a couple of hours.

The parent leaves. Maltesers get eaten. Stomachs get overwhelmed. The toilet gets heavy use. Who do you hold responsible?

Now replace the parent with a pollster, the Maltesers with a pdf full of crosstabs and the children with the rest of us. If we all inappropriately gorge on the crosstabs, pull out ‘conclusions’ from the crosstabs that are really built on sand rather than evidence, is it really good enough for pollsters to tut tut about inappropriate crosstab diving? Or is the problem with the crosstabs themselves?

Let us start with the easy end of crosstabs. Yes, pollsters publishing them is a good idea. And again, there are some very simple steps to take to improve them, starting with ones probably too pedantic to be worthy of rules. Even if it does not put something in its rules, the British Polling Council could certainly encourage more pollsters to discover the wonders of a little light formatting, and for those whose crosstabs are provided as spreadsheets, to save their crosstabs with the highlighted cell not being randomly buried somewhere in the middle but at the top left (oh so petty of me to say I know, but it is oh so irritating).

And please, let us never again have this sort of crosstab monstrosity.

On the more substantive front, there are two ways in which the apparent precision of crosstab numbers repeatedly misleads others. First, the numbers in the crosstabs are often missing key weightings and other adjustments that have to be applied before you get the final headline figures. But likewise it is often unclear how raw and rough the crosstab figures are. Better explanatory text, even if simply a health warning about raw data, right there in the crosstab documents would make it harder for people to misunderstand them.

Second, because crosstabs often get down to quite small numbers of respondents, the apparent precision of the numbers hides the margin of error related caveats that should go with. Some pollsters do add superscript letters to indicate that some numbers are statistically significant and some not. This practice is not widespread and again is not particularly user friendly even when it is used. The novice reader is not going to know if a little ‘a’ next to a number is good or bad, and how an ‘a’ on its own compares with a ‘bcd’ on another number.

Again, there is scope here for the BPC to take the lead and push pollsters to include clear, plain English labels. It would be a more dignified version of choosing to label crosstabs either ‘I would not be professionally embarrassed by quoting the number in this cell on its own because there is enough data behind it’ or ‘oh no, everyone in the office would laugh at me if I went round drawing conclusions from this number’.

Giving polling a safety curtain: baseline questions

In the second half of the nineteenth century, a new theatre typically lasted just five years before it suffered a major fire. One of the very worst such fires, at the Theatre Royal in Exeter in 1887, killed around 150 people3 despite it being a new theatre, only two years old. One result was a regulatory requirement for fire safety curtains. The ostentatious display of the fire curtain before the start of the show, something that carried on in theatres long past it becoming a curio, became a way both to demonstrate compliance with the law and also a way to reassure theatre goers that they were being protected.

Such deliberate, public display of good practice is a common feature of safety and regulatory work. It could, too, be adapted to political polling to show the quality of the samples being used by pollsters.

That is because one of the fun sidelines in polling is to give examples of how absurdly wrong the answers that people give to polling questions sometimes are, showing how those answering the survey are clearly not representative of the public as a whole.

Martin Boon, a veteran and pioneering pollster as well as the respectable face of scepticism about the accuracy of modern polling, has an example cited in the recent book Landslide of 11% of people responding to an online survey to say they have a license to drive the Millennium Falcon.

It is possible that this deliberately jokey answer option encouraged people to give jokey answers when otherwise they answer seriously. But we have more serious evidence of the problems with (some, many or all depending on your view) online samples too.

As The Pew Research Centre in the US explains:

In a February 2022 survey experiment, we asked opt-in respondents if they were licensed to operate a class SSGN (nuclear) submarine. In the opt-in survey, 12% of adults under 30 claimed this qualification, significantly higher than the share among older respondents. In reality, the share of Americans with this type of submarine license rounds to 0%.

Some online samples are badly flawed. Good pollsters who use online samples may already be composing in their minds as they read this the points they want to post in a comment about all the safety and quality checks they take to avoid such sampling problems. But how are we, the outsiders, meant to know which is the high quality sample that has nearly no submariners and the dodgy sample overrun with submariners?

Perhaps the answer is a polling version of the safety curtain. A small number of standard questions could be drawn up by the British Polling Council, for which we know what the answers should be, and which all published political polls have to include, showing us both the raw answers to the standard questions and the answers post-weighting and other adjustments.

There would I am sure be much debate about what those questions are, and the risk of samples only conforming on the criteria being scrutinised. There is always the regulatory risk that people only focus on what is being officially measured and so things get worse elsewhere.

But we know there are problems with bad sampling. We know that bad sampling is often part of the story with polling misses. And we know that bad sampling was (almost certainly) behind the story that Pew tells alongside that 2022 experiment, of how an erroneous story about Holocaust denial spread into media stories around the globe:

We took particular notice of a recent online opt-in survey that had a startling finding about Holocaust denial among young Americans. The survey, fielded in December 2023, reported that 20% of U.S. adults under 30 agree with the statement, “The Holocaust is a myth.” This alarming finding received widespread attention from the news media and on social networks…

We attempted to replicate the opt-in poll’s findings in our own survey … Unlike the December opt-in survey, our survey panel is recruited by mail – rather than online – using probability-based sampling. And in fact, our findings were quite different.

Rather than 20%, we found that 3% of adults under 30 agree with the statement “The Holocaust is a myth.” (This percentage is the same for every other age group as well.) Had this been the original result, it is unlikely that it would have generated the same kind of media attention on one of the most sensitive possible topics.

The risk of bad samples is a serious risk given what the consequences can be.

Most of the political opinion polls commissioned in the UK already include goodly numbers of questions that do not get published. The marginal extra cost of having to fit in some safety questions would be small.

As with safety curtains in theatres, safety questions, showing how good or not the samples really are, would provide an easy way to minimise a risk of a repeat of that global polling blunder over Holocaust denial.

MRPs

MRPs are the wonder prodigy of the polling scene, reported on with breathless write-ups by the media as if they are all accurate to the very last single constituency result - even when the pollsters themselves provide plenty of caveats pointing out that they are not. (In what follows, I include SRPs and even POLARIS as the issues here are related to complicated mathematical models in general rather than MRPs specifically.)

I have written often about how much the quality varies between MRPs and how important the details are over issues such as how to model tactical voting, details which get almost no attention in coverage of MRPs.

But improving transparency and understanding here is tricky. The models are complicated. The details are the secret sauce of competitive advantage and so there is a strong desire to keep them mostly secret. Yet also even if the details were widely available, the complexity of the modelling means very few people would be able to make that much of those details.

Moreover, perhaps due to their novelty, pollsters have developed good habits around MRPs. They nearly always dump the full data for an MRP at the same time as the news stories first appear. They nearly always provide their own extensive written commentary on their MRPs, putting it all online for free again at the same time as or only slightly in arrears of the news headlines. They also often write long pieces about the key methodological choices going into their models.

And yet there is clearly a risk here that not all the black boxes are equal, none are infallible and yet they get covered by the media as if they are all gold standard.

Radical options - such as standard British Election Study data being provided to each MRP modeller, who then has to show what seat numbers their model churns out, revealing how the models differ - likely would run into significant financial and administrative hurdles. (Although doing something similar with traditional polls can produce fascinating results.)

In the spirit of modest proposals, however, there is a relatively easy thing that could be improved.

Alongside the good habits, the bad habit that pollsters have fallen into is that when writing up their results for themselves, with editorial control on their own websites and in their own emails, the norm is to extensive present their figures are precise, accurate and reliable, with caveats buried a long way down.

The BPC already has a standard statement they require pollosters to stick on their traditional polls:

All polls are subject to a wide range of potential sources of error. On the basis of the historical record of the polls at recent general elections, there is a 9 in 10 chance that the true value of a party’s support lies within 4 points of the estimates provided by this poll, and a 2 in 3 chance that they lie within 2 points.

There have now been enough MRPs across three UK general elections to allow a rougher and less precise, but still useful, version of that wording to be crafted about the likely errors to expect in MRP seat numbers.

The easy move therefore is for the BPC to come up with that form of words and require pollsters to stick on all MRPs though, mindful of that bad habit, it would be best to require it to be at the top, not the bottom, of their write-ups, press releases and newsletters.

A(n unsophisticated) data repository

Our historical records of political opinion polls are full of holes. Hence why just the same day as typing up this newsletter I ‘discovered’ several extra polls from the time of the Profumo scandal that had been missing from the largest set of UK national voting intention polls. More recently, while Wikipedia is good, it is prone to problems such as the phantom polls and its links to polling tables are not closely maintained, rotting away instead as websites move, close or are restructured over time.

Hence, a very simple idea lifted and adapted from Professor Will Jennings (the man who I got AI to produce a song about): every BPC member could be required to submit their crosstabs pdf or spreadsheet to the BPC at the time of publication.

Simply dumping such files into a very simple chronological file structure in the cloud would, over time, accumulate into an extremely useful resource. Let alone what might then happen if some enterprising hobbyist, up and coming academic or smart research institution decided to make rather more of it. (Or, and hello

, perhaps AI developments mean that in the near future a folder full of polling pdfs can be given to AI bots to pull out interesting analysis.)The sooner we start collecting the files, the sooner the value starts building up.

Funding transparency

The BPC’s existing rules require a pollster to reveal the “client commissioning the survey”.

That is good, except when - as with the controversy over that Daily Telegraph mangled write-up of an MRP which appeared designed to exert political pressure - the client is funded by secret donors. Then all that transparency gives us is a label that is no more than a collective noun for anonymous donors.

The broader question of transparency over the source of spending designed to influence our political system of course gets well beyond what we should reasonably expect pollsters to take responsibility for.

Again, there is a modest simple step to take. That would be to say that if the client is not a body which otherwise has to publish information about its accounts and sources of income (as political parties, companies and charities, for example, all have to do), then the source of funds for the polling need to be named as far back along the funding chain as naming individuals or such otherwise transparent organisations.

Given nearly all the public political polling that pollsters do in the UK is paid for by companies, such as media outlets, or by political parties, then this would only risk putting off commissioning polling those who want their data to be public but their names to be secret.

Which, if their data can get front page news coverage, is really rather reasonable.

And finally…

We want polls to be talked about, to be dissected and to be analysed - and when people do that, we want them to link to the data, don’t we? When doing that, we want people to link directly the page on the pollster’s website with the data, rather than just to their homepage, from which it may be many clicks and an unclear route to the data, yes?

But… here is what one leading pollster’s website terms and conditions say:

You may link to our site home page, provided you do so in a way that is fair and legal and does not damage our reputation or take advantage of it…

Want to link to the data? Sorry no, you have to ask special permission:

If you wish to link to our site other than that set out above, please contact [us].

Oh and want to post about it on social media?

You must not establish a link to our site in any website that is not owned by you.

That would be a no again, unless you get special permission.

The pollster with the keen lawyers? YouGov.

It reminds me of circa 2010 when such T+Cs, requiring permission to link or photocopy or read on a phone were all the rage.

So if nothing else, British Polling Council, how about requiring your members to provide default permission to people to link directly to their individual pages about polls and direct to their crosstab downloads?

Of course ending on such a point reinforces that this piece is about small, incremental changes to how the political polling industry could, and should, self-regulate better.

There is more to the full topic of polling regulation than these points, such as whether optional self-regulation is sufficient. There is also the whole related topic about journalistic standards, as - outside of the years of the big polling errors - poor reporting of polls is a consistently bigger problem than those with the polls themselves.

The point, though, of highlighting them is to show that cumulatively, a significant improvement could be made without having to find a way to fix journalism or getting bogged down in the bigger debates.

So why not do it, pollsters?

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

Here are the latest national general election voting intention polls, sorted by fieldwork dates. We now have the first YouGov voting intention poll since their post-election review and methodology changes.

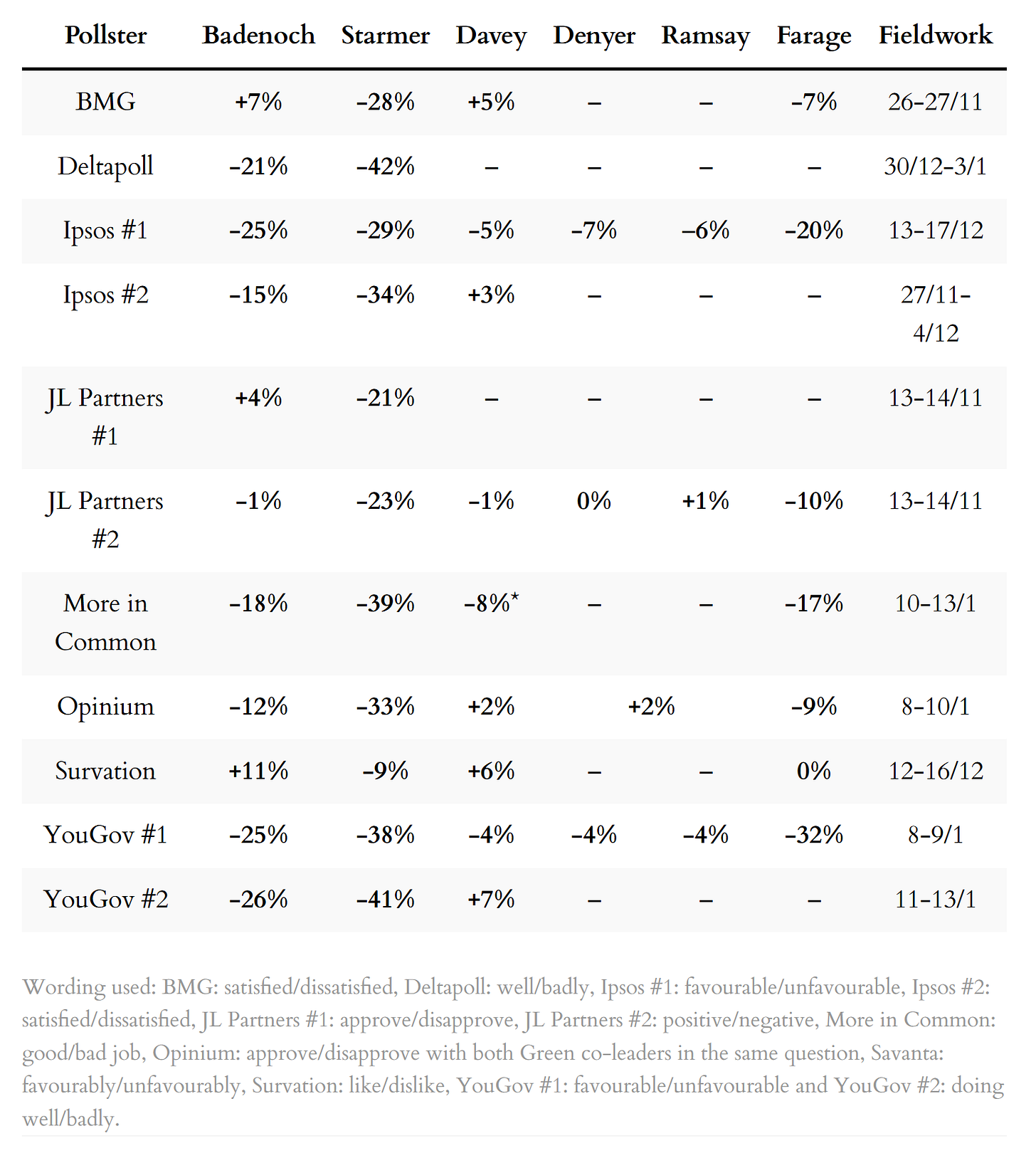

Next, a summary of the the leadership ratings, sorted by name of pollster:

For more details, and updates during the week as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Catch-up: the previous two editions

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. For content from YouGov the copyright information is: “YouGov Plc, 2018, © All rights reserved”.

Quotes from people’s social media messages sometimes include small edits for punctuation and other clarity.

Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

SNP lead Labour in Scotland, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Polling by Survation for True North Advisors has the SNP lead over Labour on

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.