Welcome to the 127th edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP), which returns to the excellent work on the electorate’s values by Paula Surridge, and to my puzzlement about the pitches being made by the Conservative Party leadership candidates.

Then it’s a summary of the latest national voting intention polls and a round-up of party leader ratings, followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis. (If you’re a free subscriber, sign up for a free trial here to see what you’re missing.)

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

How the electorate’s values are changing

There have been some great recent pieces, including by Peter Kellner and Ben Ansell, on how solid, or not, Labour’s majority is from an electoral and polling perspective, and the latest Opinium poll comes with an eye-catching graph. But as I’ve covered Labour in some detail in the last two editions of TWIP, I will hold on diving into those for a future date and instead this time turn to some new data about the electorate’s values from the ever-excellent Paula Surridge.

Her work uses a combination of two political spectrums1 - a left-right one and a liberal-authoritarian one. (She has a good explainer on this approach here.)

What does her work tell us?

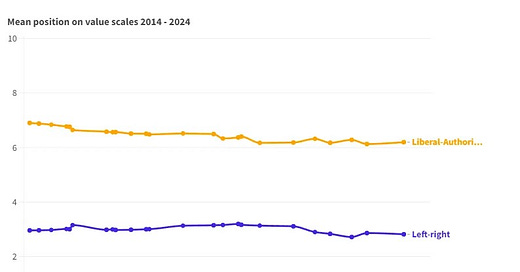

First, that trends in the popularity of different values are slow, gradual, consistent and long-term. The most notable of those is the continued long-term liberalising of Britain, something I’ve written about before.

Here a fall in the yellow line shows a move towards more liberal values over the last decade:

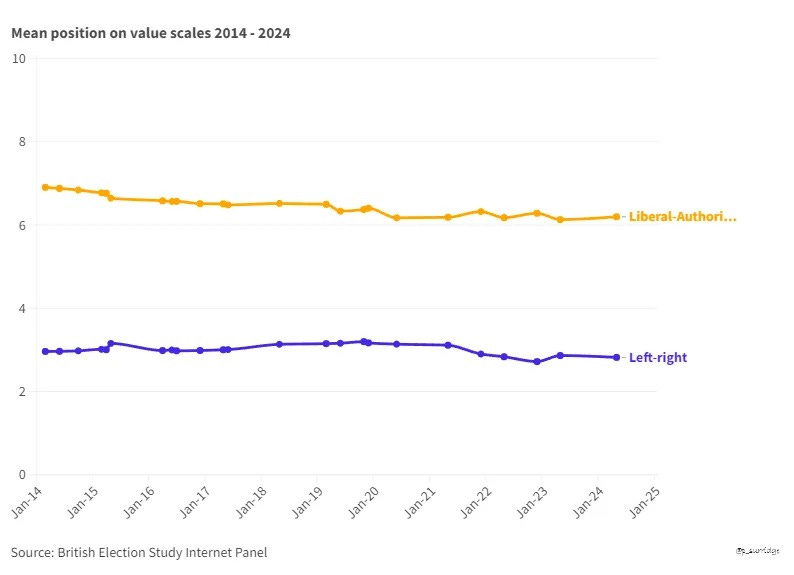

But it is when you combine the two spectrums that you get the most interesting insights, as with the relative positions of each party’s voters from the 2024 general election:

Two particular things strike me about this, both to do with the Reform and Conservative blobs.

One is that the biggest difference between Conservative and Reform voters is that the latter were much less right wing and only slightly more authoritarian than Conservative voters. That helps explain Boris Johnson’s 2019 win, based on promising to deliver Brexit and so go on to deliver a huge splurge of public spending on the NHS, police and more. He was promising more police and more hospitals, not spending cuts and a smaller state.

The other is that although heading over to where Reform voters would take the Conservatives closer to the rest of the electorate, it would still leave them a long way off. It risks being a route into a cul-de-sac rather than a route to a majority.

Overall, this graph (once again, sorry for the repetition) leaves me puzzled by the pitches that candidates for the Conservative leadership are making. For those pitches mostly make it sound like the Conservatives should seek to recover by pitching to Reform voters with an appeal based on being right wing, rather than moving to centre, and by being less liberal. That is pushing up to the top right corner of the graph where…. no-one’s voters are?

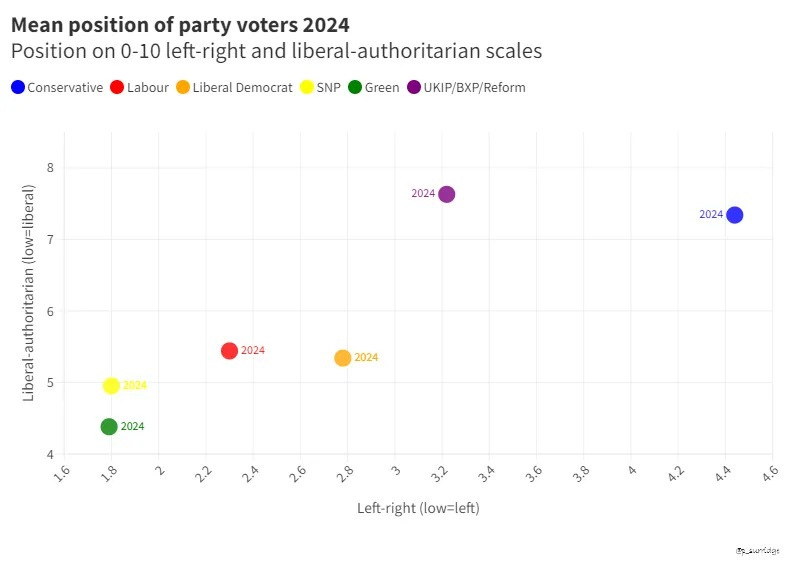

But not all points on the graph have an equal number of voters, so let’s look at another of Paula’s helpful graphics:

That makes those pitches even more puzzling when you see the size of the right-authoritarian grouping, and that it is slowly shrinking. It does though again help explain Boris Johnson’s success (look at the size of the left- and centre-authoritarian spaces) while also showing the Conservative Party’s longer-term problem (and that of Reform too) in that it is the left/centre moderates/liberals who are growing in size.2

Of course, this is not the only way of looking at the electorate, and it is important to remember that there is plenty of evidence that much of electoral choice is about competence. For all of the questions about where the Conservative Party is or wants to be on the above graphs, a very big part of their election wins in the past and their huge defeat this time has been whether they are seen as competent. Or, in the language of political science, it’s about valence issues.

As I wrote back in 2015, at the time picking over the debris from the Lib Dem electoral meltdown:

Political scientists crunching the evidence over how people decide who to vote for (such as in Affluence, Austerity and Electoral Change in Britain) find that policy issues matter much less than ‘valence’ issues.

That is, people don’t decide who to vote for based on looking at policies and seeing how closely a party or candidate’s policies match up to their own preferences. Rather, they lean on decisions over perceived competence on issues where different parties all have the same shared objective. For example, voting Conservative because you think they’ll be best at creating new jobs is a valence choice. All parties want more jobs, so picking the Conservatives is about perceived competence, not ideology.

Although there certainly are ideological choices and they do have an influence, it’s valence that dominates in British elections. Hence the problem for the Liberal Democrats in the general election wasn’t about having controversial policies which people didn’t like. There wasn’t even a small echo of the problems with the immigration amnesty policy of 2010 for example (good policy but burdened with the fatal combination of being both controversial and not amenable to a one-sentence defence). Asked where they put the Lib Dems and themselves on the political spectrum, voters kept on putting the party near to themselves overall.

Rather the problems were valence ones – about competence and trust in particular.

Add these two perspectives together, values and valence, and you can certainly see a future for a competent centre-left liberal approach.

Whether there is one for the pitches of the Conservative leadership candidates seems much less clear. But while my 2015 post-mortem writing above and elsewhere has aged pretty well, that thoughts about the candidates may be a thought which ages as badly as some of mine from the summer of 2019.

Either way, analysis such as Paula’s (of which more here) will certainly help explain what happens.

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

Here are the latest national general election voting intention polls:

Next, a summary of the the leadership ratings, which vary depending on the wording but the overall pattern is consistent:

For more details, and updates as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

Labour's post-election (non-)honeymoon, part 2.

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Is there a rise in support for Reform among young people?, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.