Welcome to the 78th edition of The Week in Polls, where this week’s gentle glance of disappointment is directed towards former Financial Times journalist and now would-be Conservative MP Seb Payne who, as spotted by Adam Bienkov, wrote that “any decent person” should be shocked “that 27 per cent of Britons ‘don’t know’ whether Hamas is a terrorist organisation” and called those don’t knows “a vocal minority”. What he didn’t mention was that people agreed it is a terrorist organisation by 66% to 6% and that 27% who don’t know compares with, for example, 26% who have not heard of the Home Secretary.1 Not so much a vocal minority whose views on terrorism should shock us as a finding in line with general levels of interest in the news.

Then it’s a look at the latest voting intention polls followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis. (If you’re a free subscriber, sign up for a free trial here to see what you’re missing.)

As ever, if you have any feedback or questions prompted by what follows, or spotted some other recent polling you’d like to see covered, just hit reply. I personally read every response.

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book here.

Or for more news about the Lib Dems specifically, get the free monthly Liberal Democrat Newswire.

Is the YouGov panel good enough for peer-reviewed academic studies?

Aside from the size of the budgets and the egos, there are two big differences between political polling in the US and the UK.

One is the much higher and better standards of transparency over polling details in the UK, thanks in large part to the British Polling Council.

The other is the extent to which polling has migrated to using online panels. In the UK, those are now the dominant form of polling, with only the occasional phone poll and relatively few innovations such as river sampling. In the US, there is a much greater variety of polling methodologies and experimentation with trying to get representative samples.

One way of viewing this is simply that the UK is ahead of the US, having moved over sooner to such a heavy reliance on online panels and that the speed, cost and convenience of such panels means the US will eventually catch up.

But before we Brits get too smug about being more transparent and more modern with our polling, it’s worth pausing to ask whether we can really trust online panels - even high quality, more costly ones - to be properly representative of the public as a whole.

That question is also at the heart of a dispute that flared up this week over an academic journal. It helpfully highlights what can be done with high quality panels to ensure their representativeness, but also highlights how limited even this country’s good transparency rules are when it comes to panel quality.

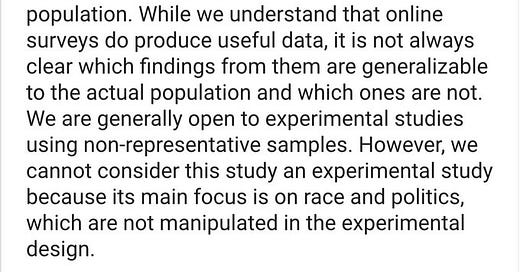

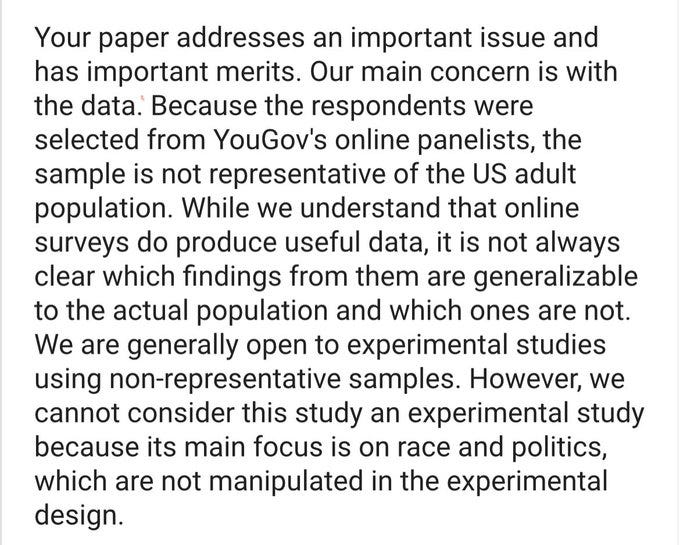

Professor Justin Pickett, of the University at Albany (and whose allegations of data forgery by another academic, who he had called his co-author, mentor and friend,2 triggered a high profile dispute and sacking), submitted an academic paper to Social Science Research.

The paper made use of YouGov data but was rejected by the journal for doing so.

As he tweeted, he was told this was because YouGov’s sample “is not representative of the US adult population”:

It’s an odd rejection given that the journal has published other papers using YouGov data, though perhaps it’s a recent change of editorial policy.

It’s also an odd rejection as it would imply, for example, rejecting any paper that used the highly respected British Election Study (BES) data that comes from YouGov or any paper using the (American) Cooperative Election Study (CES) run by Harvard that again contains data which comes from YouGov.

But the journal’s rejection also triggered a letter back from Pickett which helpfully sets out the sort of quality checks that can give us confidence in the quality of YouGov’s panels.

You can read his response in full in the images attached to his tweet here but it amounts to:

Academic research has tested out online panels versus face-to-face probability samples (the ‘gold standard’) and found they can perform as well (such as in the research here).

That’s in part because the YouGov panel uses a matching and weighting process against various known population characteristics to ensure its representative nature.

Moreover, YouGov’s panel topped the list (YouGov is Panel I in the graphic) when online panels were checked for their predictive ability for known characteristics of the population as a whole.

YouGov’s panel also performs well when it comes to final pre-election polls being close to actual election results, and that includes out-performing some pollsters who didn’t use online panels.

In addition, the quality of the panel is shown by its widespread use in top-tier academic research in highly prestigious academic journals.

All this is about YouGov’s American panel, but similar points can be made about its British panel, and indeed about high quality panels from other pollsters.

But but but… we know very little about much of the online panel work that is done for British political polling. We do know - and it’s great that we do - things like sample size, question wording and fieldwork dates.

But the industry keeps very quiet on the source of its panels. It’s well known within the industry and among polling experts that not all internet pollsters use their own panels. Rather, they in part or in full buy-in access to panels run by others. None of that however has to be detailed or declared by pollsters under the British Polling Council’s rules, and the culture of the industry is that it’s normal to keep such panel sourcing secret as part of normal commercial confidentiality.

Which means we don’t really know how good the panels being used by all the pollsters are as we don’t really know where some of them come from and whether they pass the sort of tests that the YouGov one does.

We also don’t know how much the apparent variety of different internet pollsters is a mirage. How many of the different pollsters are really buying in panel data from the same provider and so not really being as different from each other as appears?3

We don’t know. Which is a shame. And perhaps one day will also be part of the story of a collective polling failure, when a polling post-mortem finds that one problematic panel data provider ‘infected’ a series of other pollsters all of whom bought in data from the same source but badged it with their own names and so the clutch of polls all appearing to corroborate each other were in fact all wrong. Perhaps.

Certainly though it’s a reminder why it’s good to be cautious about any new pollster, especially a new online pollster, who hasn’t yet been through a set of election results against which to judge their polling.

Know other people interested in political polling?

Refer friends to sign-up to The Week in Polls too and you can get up to 6 months of free subscription to the paid-for version of this newsletter.

National voting intention polls

Once again, it a week without a poll putting the Conservatives on more than 30%, extending the run stretching back to late June (when a Savanta poll gave them 31%).

Here are the latest figures from each currently active pollster:

For more details and updates through the week, see my daily updated table here and for all the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

What should worry Labour in the polls?

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Two graphs of doom for the Conservatives?, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.