Welcome to this week’s edition which is another deep dive. People seemed to like it when I wrote a much longer than usual piece reviewing Matt Goodwin’s latest book, so this time I’m digging into MRP. What is it? Can you trust? Will it be right? And other easy questions.

But first, this week’s chuckle of amusement is triggered by Russian polling humour.

As ever, if you have any feedback or questions prompted by what follows, or spotted some other recent polling you’d like to see covered, just hit reply. I personally read every response.

Been forwarded this email by someone else? Sign up to get your own copy here.

If you’d like more news about the Lib Dems specifically, sign up for my monthly Liberal Democrat Newswire.

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

MRP: how good is it?

The birth of a new polling technique

A recent British general election saw the first public outing in the country of a new, highly sophisticated polling methodology. Using advanced statistical techniques, it generated individual constituency results from a national poll sample that would not usually be considered large enough to use to predict an individual seat. Reassuringly for the new methodology, its findings were in line with the conventional national opinion polls.

Then came 10 p.m. on election night. The polls closed. The exit poll was published, and the national polls looked wrong. The safe Conservative election win they had foretold instead turned into a hung parliament. And that fancy new methodology? It was not so fancy after all – it was wrong, along with all the rest.

That was, very nearly, the stillbirth of MRP polling in the UK.

For ahead of the 2017 general election, there were two sets of the new-fangled MRP polls. One was for Lord Ashcroft. It wrongly pointed towards a huge Conservative majority of between 162 and 180 seats. The other was by YouGov for The Times, which debuted with front-page coverage pointing – correctly – towards a shock result and a hung parliament.

It was a lucky break for MRP practitioners that the one that was right was the one that got attention, and the one that was wrong was the one that was mostly ignored. Not only was the poll that got the attention the one that was right, but it was right in a memorable, headline-grabbing way.

What is MRP?

But what is MRP?1 The acronym stands for ‘multi-level regression and post-stratification’. It is a form of modelling which allows you to use a national sample to work out accurate estimates of support for parties or candidates in small geographic areas.

MRP has its origins in trying to rescue insight from high volume, low quality data. But in the world of political polling it’s about predicting winners in individual seats.

The key to the model is the understanding that although the specific combination of different factors which impact how we vote (our gender, age, past voting record, occupation, whether we live in a marginal constituency and so on) may not be shared with many other people, each individual factor is shared by many.

Doing a poll that has a large enough sample to allow you to directly find out how, say, a male in his forties who used to vote Labour, works in the public sector and lives in a rural, safe Conservative seat is voting, would require a very large sample to reach enough people to meet all those criteria. MRP, therefore, does something different. It instead looks at what men are doing, what people in their forties are doing, what those who used to vote Labour are doing and so on. For each of these criteria on their own, you do not need nearly as large a total sample to obtain enough results from within it. The modelling then combines the answers from each of these different criteria to work out the views of the voter with that particular combination of male in his forties who used to vote Labour, works in the public sector and lives in a rural, safe Conservative seat.

What MRP calculates is probabilities, such as that a male in his forties who used to vote Labour, works in the public sector and lives in a rural, safe Conservative seat is 35 per cent likely to vote Conservative, 55 per cent likely to vote Labour and so on. Those probabilities are then gathered together for all the voters in each constituency, giving each party an overall probability of winning each seat.

The headline seat totals are then based on those seat probabilities. For example, if a party is predicted to have a 90 per cent chance of winning in ten seats, that adds nine seats (90 per cent of 10) to its headline total.

All of this requires much larger sample sizes than a regular national poll.2 However, the ability to extract individual constituency figures from these larger samples still compares very favourably with the sample sizes that would be required to do a poll in each constituency.

Can MRP really understand individual seats?

One question that often arises is whether an MRP model is sophisticated enough to pick up on a particular constituency’s idiosyncrasies. However, it is designed to put together constituency figures based on each seat’s make-up. Therefore, comments such as ‘that can’t be right for my constituency as we have many more older people than average’ misses the point. MRP is designed to cope with just that.

What it cannot cope with are very specific individual circumstances, such as if a large manufacturing site with a local workforce has just closed in a seat, putting lots of people out of work and with the government refusing financial support. That is the sort of one-of constituency event too specific even for MRP. Between the extremes of something that is just about the one constituency (significant job losses at a local site, government to blame) and something easy for MRP to model (variations in average ages of the population in different constituencies), how can you tell if a factor is too specific or not for MRP to cope?

My rule of thumb3 is to look at the average sample size in each seat, see how many multiples you need to reach 1,000 (a standard poll sample with reasonable overall margins of error), and then conclude that if a factor is present in the number of seats equal to or greater than the number of multiples, then MRP should be able to cope. For example, with a national sample of 50,000 and 650 constituencies, that gives an average of 77 from the sample per constituency. That means you need thirteen constituencies to reach 1,000. Hence a major factory closure hitting four constituencies is still too specific for the MRP model to understand. Widespread flooding, causing chaos and homelessness across two dozen constituencies, though – that it should be able to cope with.

How can MRP go wrong?

Crucially, as the fate of the pair of MRP models in 2017 showed, for all its sophistication, there is no guarantee that it is right. Not only are there the usual risks with a sample being of due to random bad luck or differential response rates, but there is the risk that the list of characteristics chosen to be modelled renders it a bad list. Do they accurately capture the factors at play influencing someone’s votes in this particular election? Of course, those configuring the MRP model for an election can experiment with how different factors work out and compare their results with national polls. It is, though, a skilled task to put together an MRP model, and one that can easily be done incorrectly. Even when successful for one election, an MRP model can fail at the next.

One thing, in particular, should remain as a worry at the back of the mind of anyone who wishes to place a high degree of faith in MRP polling. A consequence of its statistical approach is that MRP performs better the greater the variations are between constituencies (or states, or other geographic blocks being projected) rather than within them. An election that is geographically polarized, in which different parts of the country move in different directions, makes for better MRP modelling than an election which is, say, polarized by gender (as constituencies do not vary much in their gender breakdown).

A lesser but still potential source of error comes from working out how many people with each combination of those factors are in each constituency. The sorts of sources used, such as the census, are episodic and may be many years out of date. That requires judgements about whether to extrapolate updates to the data and if so, how. (This is harder than it may seem, and so was one of the sources of errors for conventional polls at the 1992 general election.)

Moreover, the details of which factors have been used and the relative importance given to them is, currently at least, treated largely as a secret black box. Even with the YouGov MRP model in 2017 and 2019, for which a large amount of information was published live during the election campaigns, there was little detail on the key calculations at the heart of the model. (And even if there had been, evaluating sophisticated statistical models is a rarefied skill.)

Compared with conventional political polling, MRP is, in some ways, more challenging to get right. As with conventional polling, the overall polling methodology has to be right, including sampling and turnout weighting. Then, in addition, MRP also has to get right the constituency modelling. In return for that added complexity – and so added risk – MRP should give a better idea of seat numbers, which is important in close elections or ones in which the country’s political geography is changing.

However, there is a delicate balance to be struck when considering political geography and the use of MRP. If no change in political geography is occurring, then simple extrapolations of seat numbers from national poll numbers will work well, and MRP does not add much predictive power. On the other hand, if too much change in political geography is occurring, or it is of the type that MRP struggles with, then it could undo the MRP modelling.

Like Goldilocks with her porridge, in order to shine MRP practitioners need change to be neither too little nor too much. The change needs to be just right.

How are current MRPs performing?

Since the 2019 general election we’ve had four local election MRPs, three from Electoral Calculus which haven’t performed great and one from YouGov which did rather better. But those are only four and local elections are local elections.

For the general election picture, the MRPs we are getting throw up three reasons – additional to the above - for caution over interpreting, relying or even betting on their results.

One is that some have distinct oddities in the details, as I highlighted when looking at a Best for Britain/Focaldata MRP in a previous edition, quoting Peter Kellner who said:

The latest Focaldata projection shows the Conservatives implausibly gaining support in Liverpool and parts of inner London, even as their voters flock to other parties everywhere else.

Lesson one then when a new MRP comes out is to look for those tail results: where does the model show the party doing differently from the overall broad picture and do those exceptions make sense?

The second is what you could call the Wimbledon problem.

The result in 2019 at the general election was Conservative 38%, Lib Dem 37% and Labour 24%. With the Lib Dems missing out by just 628 votes and continuing to make local election progress in the area, what would you expect the result to be at the next election? We’ve had several MRPs so far this Parliament, some showing the Lib Dems winning and some showing Labour winning in the seat.4

Now if the Liberal Democrats have a shocker at the next general election, and it turns out we failed to learn the lessons of the Thornhill Review, then perhaps you might think ‘Lib Dem melt down, Labour leapfrog Lib Dems’ is plausible. However… the MRPs that showed the Lib Dems winning Wimbledon overall showed similar national performance for the party as the MRPs showing Labour ahead. In other words, the latter are claiming that with Lib Dem support holding up nationally, maybe even rising, and the party doing decently, Labour would still win Wimbledon.

Electoral Calculus, for example, thinks at time of writing both that the Lib Dems will win 30 seats at the next election (Lib Dem triumph with lots of seat gains all around) and yet at the very same time that Labour has a four-in-five chance of winning Wimbledon (Lib Dem disaster failing to win one of the most marginal seats in the party’s sights). Overtaking the SNP nationally in seats yet missing out on a top target.

That’s quite a brave prediction.

Or – and I think it isn’t just the Lib Dem in me saying this – a prediction that makes it reasonable to doubt the model, especially given what we’ve seen in Parliamentary by-elections and local elections about the willingness of Labour supporters to switch very heavily to the Lib Dems to help defeat Conservatives.

So lesson two is to remember that not all MRPs are equal and when it comes to some seats – and Liberal Democrat targets in particular – there’s a large degree to which the MRP results tell us what choice the modellers have made rather than what voters are saying.

It’s the difference between the modellers, not the voters in their samples, that produces such varying Wimbledon figures.5

Owen Winter has made a similar point in an excellent piece about oddities in MRP details, using Twickenham as an example of an MRP giving an improbable looking result.

His piece is also a good read related to a third issue. That third issue is the vexed question of uniform versus proportional swing. Let’s take an example of one party’s vote share to explain the context for this.

Imagine the Chocolate Lovers Party won 40% at the last general election and that polls currently put it on 30%, that is 10 percentage points down (40 minus 30) but also having lost a quarter – 25% - of its support (10 as a percentage of 40).

Now think of three constituencies, Bournville Central where they got 80% at the last election, Hazelnut North West where they got 40% and Littlehampton and the Isle of Custard where they got 8%.

Given currently polling, what should we expect their results to be in each of these three seats? A proportional change would mean that they lose a quarter of their support in each seat – i.e. 80% becomes 60%, 40% becomes 30% and 8% becomes 6%. Proportional changes often seem intuitively reasonable to people, and 60%/30%/6% certainly seems a plausible set of results.

Uniform change is different. It means that as the party is down 10 percentage points you remove 10 points from its share in each seat. Bourneville Central sees the party on 70%, Hazelnut North West is now 30% and Littlehampton and the Isle of Custard is… minus 2%!?

Despite the problems like that with uniformity – or if you’re looking at swing, uniform swing – it has the last laugh. Because proportional swing has consistently failed to out perform uniform swing at British general elections.6 Which is why uniform swing has been at the heart of seat projection models to turn national vote shares into MP totals.

Enter stage left, MRP. So far in this Parliament, MRP models are showing swing that is much more proportional than uniform. Given the levels of Conservative support (down heavily), that also translates into showing much heavier seat losses for the Conservatives. The more proportional the MRP, the more meltdown for the Conservatives.

Working out what to make of this is hindered by us not really knowing why uniform swing has worked so much better than proportional swing over the years. (Peter Kellner’s great piece on this doesn’t so much explain it as redefine the conundrum, showing how a particular distribution of voter types produces uniform swing but therefore also prompting the follow up question of why that is the distribution we have.)

One possibility is that MPR is right. The clever statisticians and diligent pollsters7 are telling us that something very unusual is happening at the moment. That might be right, as Labour’s Scottish meltdown and the Lib Dem universal meltdown in 2015 were both proportional rather than uniform. Is Rishi Sunak the new Jim Murphy/Nick Clegg? Perhaps.

Another possibility is that history is right and our reaction to MRP giving us proportional results should be to doubt it. Uniform swing has metaphorically seen off quite a few generations of clever people touting the theoretical virtues of proportional changes, only to see election results come out its way. UNS is simplistic yet it works; it’s psephology’s version of the early 1980s Watford football team’s long ball, route one style.

The third possibility is that the nature of mid-term political views is that they produce swings more proportional than uniform in MRPs but that as a general election nears and views solidify, the same MRP models will give us increasingly uniform outcomes. That’s a point that pollster and now Labour candidate Chris Curtis touched on looking at one MRP showing a Conservative meltdown: “There seems to be a massive problem with midterm seat projects showing something closer to a ratio [i.e. proportional] swing when I expect the swing to be more uniform.”

At this point, alas, I must let you down dear reader and reveal that not only do I not know which of these three will turn out to be right, but I also can’t give you a strong argument for one over the others. I’d slightly edge towards history winning out and the results being more uniform than proportional (I do have a history PhD in 19th century elections, after all). But when a party melts down we’ve seen proportional swings, and look at those Conservative vote shares in the polls…

Not even the saintly Professor Sir John Curtice can save us, for as he wrote about the uniform versus proportional conundrum: “In truth, we are in uncharted waters. Given the unprecedented scale of the fall in Tory support, nobody can be sure what the outcome in seats would be if the current polls were reflected in the ballot boxes.”

An aesthetic choice

Given these issues and the brief track record of MRP so far, even combining the British examples with those in other countries, there is no firm conclusion one can draw about MRP’s overall utility compared with other polls.

It is, at the moment, more an aesthetic choice.

Do you view a national election as a national event, played out on the national stage? After all, voters generally are better able to name national party leaders than local candidates. If so, a conventional national poll captures the essence of it.

Or do you view a national election as the aggregation of each voter’s individual voting decisions, added up at constituency level to produce an overall result? After all, that is how the maths of national vote shares and national seat totals work: they are simply the sum of all the local results based on all the individual votes in each seat. If so, MRP’s approach of modelling each individual and aggregating up captures the essence of it. Moreover, when MRP gets it right, this approach means you can explain why things are happening much better, by breaking them down into the individual voter switches that caused seats to be gained, held or lost.

Yet elections are, in truth, both an individual and a national event. This is why the future of polling is likely to involve both MRP and traditional polling – and both can, and will, sometimes go wrong.

Parts of the above are extracted from my book, Polling UnPacked: The History, Uses and Abuses of Political Polling, which includes further details about MRP, including the third, less noticed, MRP from the 2017 general election.

Know other people interested in political polling?

Refer friends to sign-up to The Week in Polls too and you can get up to 6 months of free subscription to the paid-for version of this newsletter.

National voting intention polls

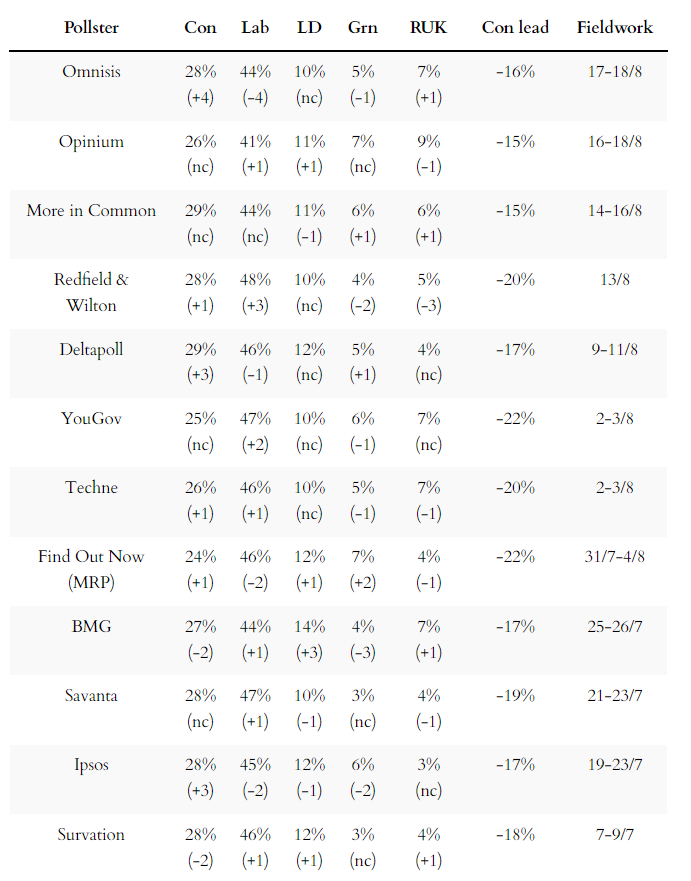

It’s now 54 polls since we last had one that put the Conservatives on more than 30%.

Here are the latest figures from each currently active pollster:

For more details and updates through the week, see my daily updated table here and for all the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Last week’s edition

More reasons to doubt that the don’t knows will rescue the Conservatives.

An important change in polling over immigration, and other polling news

These weekly round-ups are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.