Welcome to the 166th edition of The Week in Polls (TWIP) which sees Ipsos return to voting intention polling and takes a dive into a BBC documentary that appeared to feature a significant polling blunder. What happened when I contacted the BBC? Read on to find out.

Then it is a summary of the latest national voting intention polls and a round-up of party leader ratings. Thank you to Keiran Pedley (Ipsos), Jordan Meyers (Freshwater) and Luke Tryl (More in Common)1 for promptly answering my pedantic queries about their data this week.

Those are followed by, for paid-for subscribers, 10 insights from the last week’s polling and analysis.

This time, those ten include fascinating new research that undercuts one of the central tenets of the political strategy of Thatcherism.

The Week in Polls often often draws on the work of those at UK universities, so a little thank you for me in return with a special offer for anyone with a .ac.uk email address: you can sign up for the paid-for version of this newsletter at half price:

Before we get to the main show, I think we can all sympathise with ElectionMapsUK:

And with that, on with the show.

Want to know more about political polling? Get my book Polling UnPacked: the history, uses and abuses of political opinion polling.

How does the evidence stack up for the polling claim in the new Adam Curtis/BBC documentary?

Notable documentary maker Adam Curtis has a new series out, Shifty, which is attention grabbing for a variety of reasons. In the BBC’s words it features:

Gay Scottish Disco. Intersex dog. Mrs Thatcher. Encounter group. Ghosts of the Empire. Jimmy Savile. The Cheese and Onion computer. Video dating. Ian Curtis. Monetarism. Dead pilot. Stephen Hawking and Black Holes. National Front. Fat-shaming ventriloquist. Dub clash sound system. Party elephant. W****r on the line. Racist attacks. Bucks Fizz.

But what grabbed my attention was the early reference to opinion polling in episode 1.

From around three and a half minutes in, we get these captions in sequence (with no narration):

Mrs Thatcher was behind in the 1979 election campaign

Then she made a speech attacking immigration

She knew it would appeal to the swing voters in the old industrial towns

(Clip of Margaret Thatcher making a speech on immigration)

Immediately she took a lead in the polls

This struck me as odd, because my memory of studying the 1979 election campaign was that neither were the Conservatives behind nor that there was a turning point with a speech on immigration.

I was not the only person to spot this, and Oliver Johnson’s piece includes relevant screenshots.

But what of the evidence?

Let us turn to the largest database of national voting intention polls in Britain, Pollbase, handily maintained by, er…, myself. This has 44 voting intention polls conducted from the start of 1979 until general election polling day (29% more than Wikipedia has).2

The very first poll of the year had Labour ahead, by 6.6%, but then of the next 43, only one other had Labour ahead (by 0.7%). While the Conservative vote does slip during the year, the party stays in the lead and the accompanying story is of a rise in the Liberal Party vote, with Labour static.

To make matters worse, as Oliver Johnson tracked down, the speech clip used was not from 1979 but from early 1978.

That seems an open and shut case.

The BBC Press Office, doing a better job than Google’s, kindly put Adam Curtis in touch with me and he responded:

You are completely right. I made a bad mistake in not spotting that the first caption in that section had been oversimplified. In my original edit the caption read - IN THE POLLS LEADING UP TO THE 1979 ELECTION CAMPAIGN - because, as you rightly say, Mrs Thatcher made the speech in 1978. Somehow some of the wording got lost. I don't know how. But it is completely my fault, and as you also say, viewers have a right to expect accuracy in factual programmes. In this case I failed and I would like to apologise for that. I will get it changed right away. Thank you very much for pointing that out.

Having made mistakes myself, I won’t be throwing stones over that.

But what about the idea that the speech was a turning point in the polls, now that we know it is 1978 to look at?

Adam Curtis again has an explanation:

In the contemporaneous report in the New York Times after Mrs Thatcher's speech, by one of their most senior journalists, R W Apple jr, he wrote:

“She hotly denied that suggestion, arguing that it was ‘absolutely absurd’ for political leaders not to discuss matters that worried voters. Her critics in the press and in the House of Commons conceded the point but complained about her use of ‘code words’ such as ‘swamped’ and the imprecision of her proposals…

“A survey by National Opinion Polls showed the Tories with an 11‐point lead over Labor, 50 percent, to 39 percent. Just before Mrs. Thatcher's television comments, Labor had led by two points in a poll by the same organization. A Gallup poll suggested the depth of feeling on the subject: 59 percent of those interviewed said they considered immigrants a very serious social problem, 46 percent said race relations were worsening, and 49 percent said Britain should offer cash to immigrants who would return home."

R W Apple was the New York Times bureau chief in London at the time. He was a highly respected journalist who believed that the Times was ‘a paper of record’.

It also corresponds with a conversation I had with Sir Keith Joseph later in the early 1990s when I was researching a film on the early Thatcher administration. Joseph was one of the people closest to Mrs Thatcher at that time as they prepared for the coming election. He told me that that speech had a big effect on the polls, and that they were worried at that time about being behind.

The full story from the New York Times, of 21 February 1978, is online here and certainly provides some basis for what appears in the documentary.

But how good is that basis? Let us break out the polls again.

First, though, note that although the clip in the documentary is from a speech to a Young Conservatives Conference on 12 February 1978, the New York Times is referring to, “a television interview three weeks ago”. This is her appearance on Granada TV’s World in Action, broadcast on 30 January 1978, with the controversial comments:3

I think it means that people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture and, you know, the British character has done so much for democracy, for law and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in.

So how did the polls move before and after 30 January 1978?

There is indeed an NOP poll which shows a dramatic move: from a Labour lead of 1.5 points before the speech to a Conservative lead of 11 points after the speech. (Note that this later poll had fieldwork 4-7 February 1978, so was after the TV interview but before the speech.)

But, but, but…

There are two other pollsters we can look at, and they tell a different story.

MORI polls from February and March 1978, if they took place, have not survived in the public record (neither in Pollbase nor in the historic archives on the website of its corporate successor, Ipsos). We can though compare January and April polls, which show a Conservative lead of 1% before and 2% after. No dramatic shift, well within margins of error, and not a move from behind to ahead.

The third pollster is Gallup. Their polls show a move from Labour and Conservatives being tied to a Conservative lead of 9 points. Not quite behind to ahead, but a dramatic move and so evidence to go with NOP, and giving us a 2-1 score in favour of the speech having had a dramatic and quick impact?

Not so fast… because if we rolling the polling clock back earlier, we see that there was already a move underway before the speech with NOP. It had gone from an 8 point Labour lead to to a 1.5 point only before the speech and then that 11 point Conservative lead after.4

So of the three pollsters, one had a sharp improvement in the Conservative position taking place both before and after the TV interview, one had no big shift and only one of the three pollsters has a clear pattern that fits the idea that the one speech suddenly moved the polls.

Nor was the speech the only thing happening in politics around that time. The 1970s were very much not a ‘one thing at a time’ period. For example, strikes peaked in the last quarter of 1977, with the most working days lost to strikes since late 1974 and only subsequently exceeded in the Parliament during the Winter of Discontent. Although there was also good news for the government with the falling inflation rate, it was only later in 1978 that real disposable incomes really started growing.5

Moreover, the broader picture is that between the speech and the general election, Labour recovered enough in the polls to lead to speculation of a general election being called early. All that ended with the Winter of Discontent in 1978/9 but the great what-if of PM Jim Callaghan calling an election before the Winter of Discontent is only such a popular historical counterfactual because there was a period - after Thatcher’s comments - when it looked like Labour would, or least could, win again.

To recap, then, the polling evidence is decidedly mixed about whether there was an immediate turning point in the polls in late January 1978 and the longer perspective makes it a dubious turning point too.

I also dug out the 1979 general election volumes of the three standard series of books on British general elections to check if I was just getting lost in the psephological details.

The venerable Nuffield series, The British General Election of 1979 by Butler and Kavanagh, mentions the ‘swamping’ interview briefly, but then goes on to stress how Margaret Thatcher included reassurances to existing immigrants in subsequent remarks, backing away from her earlier comments. As the book says, “the polls suggested that immigration was far less salient for voters than the traditional bread-and-butter issues”.6

Turning to the 1979 edition of the Britain at the Polls series, this one edited by Howard R. Penniman, it talks about how the Conservatives were on the back foot over immigration, fending off accusations rather than making it a vote winner for Margaret Thatcher’s party: “Labour … was able to take some advantage or the differences between the two parties … In areas where there were substantial numbers of Asian immigrants, Mrs. Thatcher’s presumed threat to their status seems to have worked to Labour’s benefit.”7

The 1979 version of the Political Communications series, edited this time by Robert M. Worcester8 and Martin Harrop, has, to be fair, a slightly different take. It identifies a group of Labour voting social conservatives who swung to the Conservatives in 1979.9 This analysis shows that opposition to immigration was one of the characteristics that most clearly identified such socially conservative swing voters. But it being one of the clearest ways of identifying such people does not mean it is what drove them to switch, nor that it was one speech that caused them to dramatically and quickly do so.

Of course, much of this is detail that it would not be reasonable to expect to make it into a TV documentary. Though it is more than enough to outweigh the Keith Joseph comments mentioned as evidence earlier.

There is one other, perhaps conclusive, factor to consider. Which is that while the ‘one thing that dramatically changes the world’ is a trope beloved of everyone from West Wing writers through to conspiracy theorists, the reality of electoral politics in Britain is that it is very rare for one moment to suddenly change things.

Those rare moments occur - leaving the ERM and the Liz Truss budget for example - but note too that those moment are not only rare but also almost always acts by or befalling the government.

Arguing that one speech by an opposition politician suddenly shifted things dramatically is a very bold claim. Such a bold claim, I think it is fair to say, should come with strong evidence. But the evidence we have here is, at best, mixed and in some respects weak.

The lesson of course, as ever, is not to pay too much attention to any one poll, such as that one post-speech NOP poll.

Looking at more polls always provides more wisdom.

Voting intentions and leadership ratings

Here are the latest national voting intention figures from each of the pollsters currently active, with a return to voting intention polling by Ipsos.

It comes in with an attention-grabbing record low score of 15% for the Conservatives. Not only the lowest ever with Ipsos or its predecessor, MORI, but also the lowest with any pollster since the first national vote share poll in 193910 save for one 14% and three 15%s in the last Parliament, three of which were with PeoplePolling and the other an MRP with Find Out Now / Electoral Calculus.

Ipsos has changed its methodology with, as it explains,

a new form of data collection (online random probability panel instead of quota telephone survey) that allows us to stratify the initial sample by 2024 past vote as recorded at the time, an updated voting intention question (now prompting for Reform UK), and an updated weighting scheme (that now includes digital as well as print readership in our newspaper weighting), that has updated various sources such as the measure we use for public sector workers, and a new weight based on type of constituency (marginal/non-marginal), though most of the weight categories used remain the same). This is based on our learnings during and since the 2024 General Election. This means that comparisons with previous waves need to be made with caution. In particular, at this stage we are not making direct comparisons with previous satisfaction ratings for opposition party leaders (though our tests suggest that trend comparisons can be made for ratings of the government and Prime Minister).

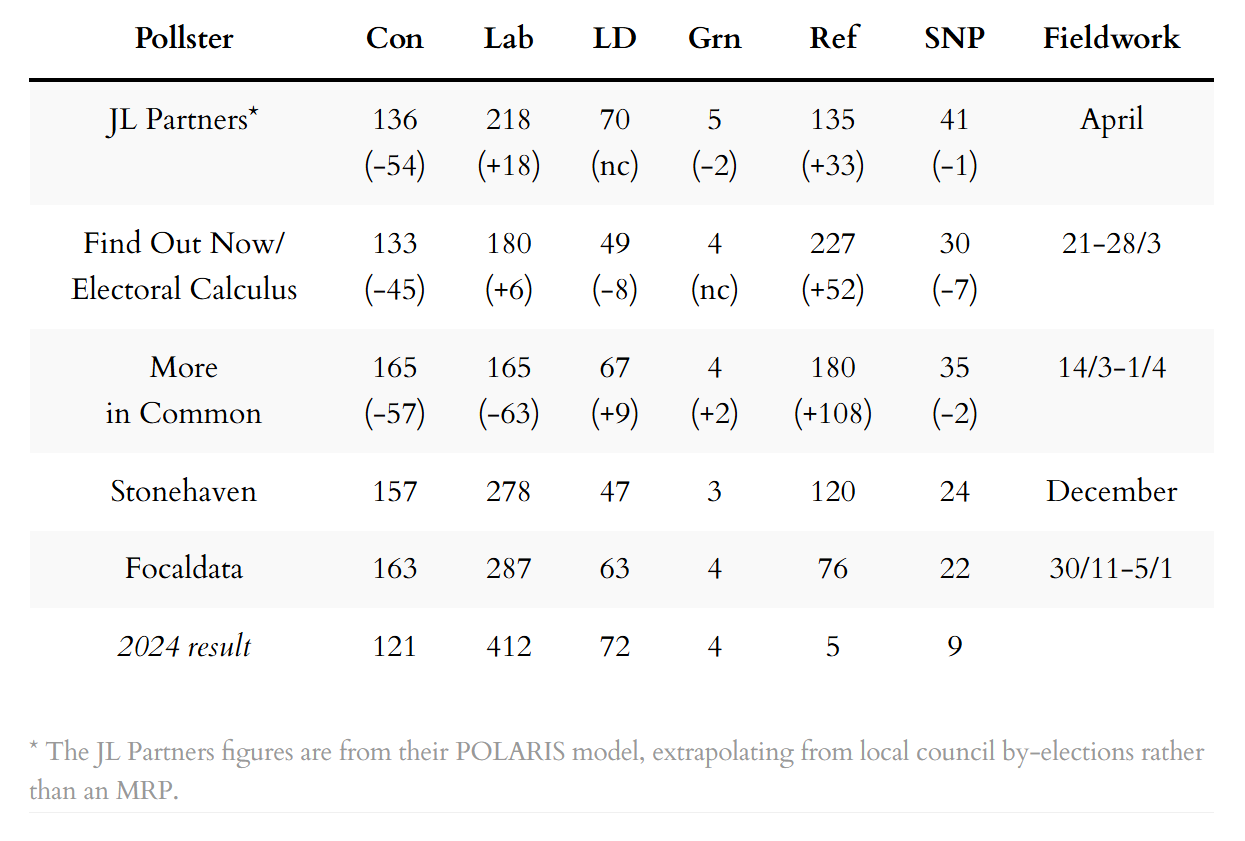

Next, the latest seat projections from MRP models and similar, also sorted by fieldwork dates:

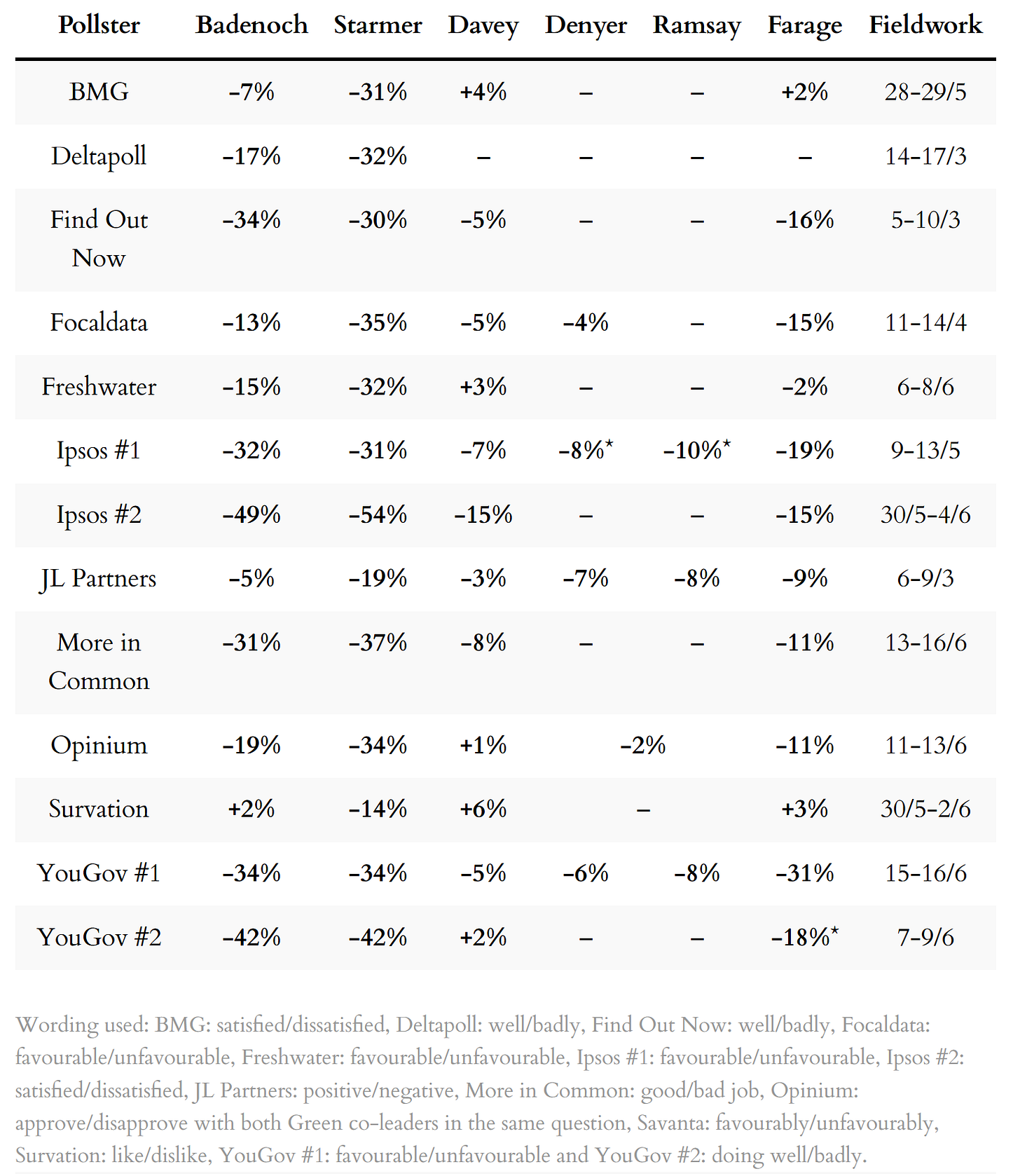

Finally, a summary of the the leadership ratings, sorted by name of pollster:

For more details, and updates during the week as each new poll comes out, see my regularly updated tables here and follow The Week in Polls on Bluesky.

For the historic figures, including Parliamentary by-election polls, see PollBase.

Catch-up: the previous two editions

My privacy policy and related legal information is available here. Links to purchase books online are usually affiliate links which pay a commission for each sale. For content from YouGov the copyright information is: “YouGov Plc, 2018, © All rights reserved”.11

Quotes from people’s social media messages sometimes include small edits for punctuation and other clarity.

Please note that if you are subscribed to other email lists of mine, unsubscribing from this list will not automatically remove you from the other lists. If you wish to be removed from all lists, simply hit reply and let me know.

Are young women becoming more left-wing and young men more right-wing?, and other polling news

The following 10 findings from the most recent polls and analysis are for paying subscribers only, but you can sign up for a free trial to read them straight away.

Richard Nennstiel and Ansgar Hudde have been looking at the (possible) gender

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Week in Polls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.